In general, the gold miners, such as Goldcorp’s Porcupine mine (above) in Ontario, have

seen the market stabilize after a rocky 2018.

Top Gold Producers Process More Ore,

Produce Less Gold, Again, in 2018

By Jesse Morton, Technical Writer

Meanwhile, the miners, generally speaking, processed a bit more ore to get those lower production numbers, and saw costs creep higher for the fourth straight year. It further fueled the theory that world gold production, at least for most of the top miners, is cresting. The trend appears to be behind two mergers, among the biggest in mining history, that occurred late last year and early this year. Those mergers temporarily pushed news from the industry to primetime audiences.

The backstory is found in the numbers from the two miners’ investor reports. Simply put, they are logging declining production, almost across the board, at their biggest mines. After a couple of years of aggressively nixing debt, they made hard moves to buy a competitor, pump up reserves, pacify shareholders, and muscle into the inside lane for the next few laps.

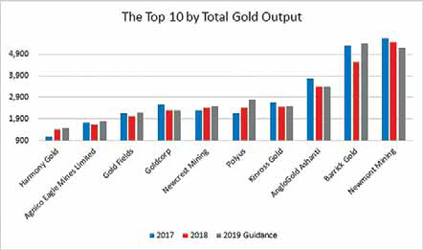

The box scores from a pantheon of top producers1, ranked by total output in 2018, provide the context and details.

No.1 Newmont (5.5M oz)

In an annual report recapping 2018,

Newmont reported an unaudited net income

(attributable to stockholders) of

$280 million and an adjusted net income

of $718 million. Net debt was unchanged

yoy. With a year-end cash-on-hand to debt

ratio of 2.5, the company described its

balance sheet as “industry leading.”

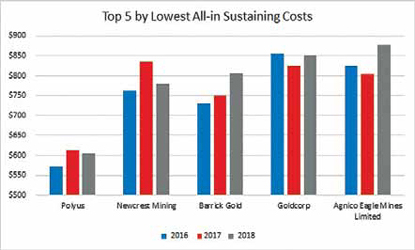

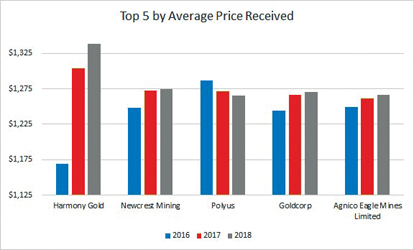

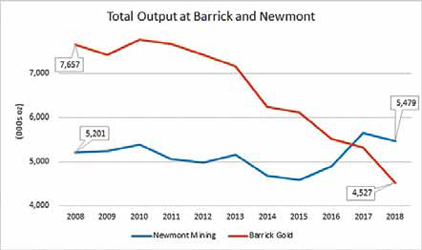

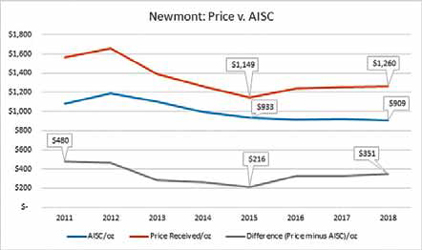

After increasing for three years, unaudited numbers suggest total gold output at Newmont fell by 3%. AISC and total price received per ounce (oz) has basically been flat since 2016. According to unaudited numbers, the AISC/oz for 2018 was $909, the average price received was $1,260/oz, and the difference between average price and AISC was $351.

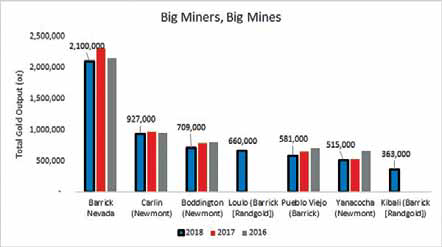

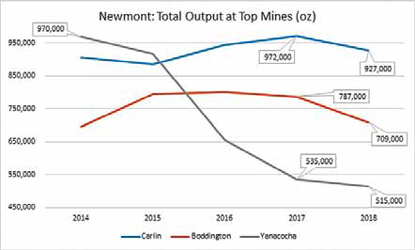

Gold production fell 5% yoy at Carlin (Nevada, USA), 10% yoy at Boddington (Western Australia), and 4% at Yanacocha (Peru), three of the biggest mines in the world. The declines were primarily attributable to “lower grade at various sites and lower leach tons placed at Carlin, Phoenix (British Columbia, Canada), Cripple Creek and Victor (Colorado, USA), and Yanacocha, partially offset by higher grade and recovery at Tanami (Australia) and Ahafo (Ghana),” the company reported. Production also fell at Long Canyon (Nevada), Twin Creeks (Nevada), Kalgoorlie (Australia), and Akyem (Ghana), the company reported.

According to the company’s Q4 results, gold production for the year increased at only four of the company’s 12 mines. In 2018, the company logged roughly $1 billion of capital expenditures, up yoy. Roughly 40% of that went to development projects, which included “Twin Creeks Underground in North America; the Merian crusher and Quecher Main in South America; the Tanami Expansion 2 project in Australia; and Subika Underground, Ahafo Mill Expansion, and Ahafo North in Africa,” the company reported.

In July, the miner reported it entered agreements to acquire a 50% interest in Galore Creek from NOVAGOLD Resources, and to join with Teck Resources, who owns the remaining stake. “Galore Creek, located in British Columbia, is one of the largest undeveloped copper-gold projects with resources previously reported by Teck of 8 million oz of gold and 9 billion pounds of copper,” the company reported. “Galore Creek holds the potential to support decades of profitable copper and gold production.”

Separately, in July, the miner reported it had completed its Northwest Exodus project, “extending mine life from the Exodus underground operation in the Carlin North area for 10 years.” The project was to add “higher-grade, lower-cost gold production in Nevada” and was “completed safely, ahead of schedule and within budget.” Also, that month, Newmont declared it achieved commercial production at its Twin Creeks Underground expansion project, “adding higher-grade, lower-cost gold production.” The project was completed on schedule and below guidance, the company reported.

The move was soon followed by media reports about a possible merger with Barrick, which inspired sensational headlines, but quickly simmered down to a proposed joint venture involving mine sites in Nevada and Colorado.

The terms of the partnership would give Barrick 61.5% ownership and operational control. The assets involved include Cortez (Nevada), Goldrush (Nevada), Goldstrike (Nevada), Turquoise Ridge (Nevada), Carlin, Long Canyon, Phoenix, Twin Creeks and “all associated processing facilities and other infrastructure,” Newmont reported. Details on how the partnership, between the world’s two biggest gold miners, would change routine operations at the biggest gold mines in the world remain scarce. Newmont reported the goal is to synergize under a “proven and scalable operating model.”

For 2019, production is expected to ramp up at Ahafo, where first commercial production was achieved in Q4 2018. The mill expansion project there should bump up numbers in H2, the company reported. Quecher Main project production should bump up oxide production numbers at Yanacocha in H2. And cost-savings linked to the completion of the Tanami Power project should show up in 2019, Newmont reported.

Total gold production for 2019 is projected to be 5.2 million oz, the company reported, at an AISC of $935/oz. Newmont reported “attributable proven and probable gold reserves of 65.4 million oz at December 31, 2018.”

No.2 Barrick Gold (4.5M oz)

While Barrick Gold reported in its 2018 recap

webcast a net loss of more than $1.5

billion, it logged adjusted net earnings of

$409 million. The company reported reducing debt by a staggering 11%, which

appears to jibe with the ongoing three-year

trend among the majors of debt elimination.

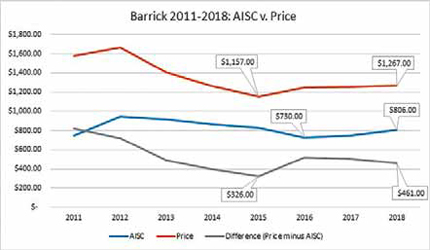

Production of 4.53 million oz, down almost 15% yoy, was within guidance, the company reported. Production has fallen nine of the past 10 years. It has been gradually declining since it peaked in 2006. AISC rose roughly 7% in 2018. It was the highest it has been since 2013. Average price realized per oz rose less than 1% in 2018, but was the highest it had been since 2014.

The difference between price received and AISC decreased roughly 9% yoy, down to $461/oz from $508/oz. That is close to the average for the company for the preceding half decade, at $449/oz. Production at what the company labels Barrick Nevada, the world’s biggest pure play gold mine complex, comprising Goldstrike and Cortez, fell 9% yoy. The company reported that the mine is “entering a period of transition as Cortez gold production moves from predominately oxide open-pit ore to mostly underground double-refractory material.”

Barrick reported the total ore mined fell roughly 17% yoy, and total ore processed fell almost 20%. Production increased by 27% yoy at Turquoise Ridge mostly due to 2017 numbers being low due to a disruption. Production fell by 11% yoy at Pueblo Viejo (Dominican Republic) and 13% at Veladero (Argentina) due to declining grade. It also fell by roughly 4% yoy at Lagunas Norte (Peru).

For 2018, the company reported a slight uptick in capital expenditures yoy, to $1.4 billion, due to increased spending at Crossroads (Western Australia), Cortez, Goldrush and Turquoise Ridge, where a third shaft is being constructed. In September 2018, Barrick announced an agreement to buy Randgold Resources, easily one of the world’s top 15 pure play gold miners by annual production, to the tune of roughly $6 billion. With the “transformational merger with Randgold,” Barrick reported it is the “industry- leading gold company.” For the moment, Barrick was, according to both its reports and the mainstream press, the “new mining champion.”

For 2019, Barrick reported that the Cortez Hills open-pit mine, which will mine higher grade ore at a “low cost,” is “scheduled for completion in H1,” which will lead to a “structural increase in costs.” A gas pipeline to Pueblo Viejo is set for completion in Q4. A mining lease for Porgera (Papua New Guinea) is expected to receive approval in Q3. A drill program is planned for Bakolobi at Loulo (Mali). The company reported it could spend as much as $1.7 billion on capital expenditures.

No.3 AngloGold Ashanti (3.4M oz)

In its annual recap, AngloGold Ashanti

reported a gross profit of $772 million on

the year. It reduced net debt a mind-boggling

17% yoy. And it increased free cash

flow from $1 million for 2017 to $67 million

for 2018.

Production fell almost 10% yoy to the lowest level it has been since the millennium, attributed mostly to the sale and closure of mines in South Africa. Excluding the numbers from those mines, production increased by 70,000 oz yoy. AISC fell 7% yoy to $976/oz, which was 5% below the 5-year average for the company. Price received per oz rose less than 1%, and was the highest it had been since 2014. The difference between the two was $285.

The miner mined and treated 7% and 6% less ore yoy, respectively. Production numbers were boosted by more metric tons treated and improved grade at sites in Central Africa. Higher grade improved production numbers at projects in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, Tanzania (at Geita, which produced 564,000 oz), and in Australia. Lower grades impacted the numbers from projects in Guinea, Mali and Argentina. Delays impacted production in Brazil. When the sold and closed mines are excluded, production in South Africa rose 2% yoy.

Minor legal action and mine sales and closures were among the leading developments for the company in 2018. The company worked out a wage agreement with “all its trade unions in South Africa” in July. That month, it had its case with the government of Ghana, over a military intervention to resolve an illegal occupation of a mine, dropped.

The company logged $721 million in capital expenditures last year, down 24% yoy due in part to South African mine sales. A big chunk of the capex went to growth projects at Central and South African sites, the brownfields expansion project in Guinea, and a new ball mill in Australia.

For 2019, the miner plans on “bringing Obuasi (Ghana) into production,” with the first gold pour set for the end of the year. A new plant at Siguiri (Guinea) is calendared for commissioning in Q1. Substation development at Mponeng (South Africa) is slated for H2. Feasibility study work will run into Q2 at Quebradona (Colombia), with engineering work to follow in H2. The miner reported it could spend as much as roughly $1 billion in capex next year.

No.4 Kinross Gold (2.5M oz)

Kinross Gold reported revenues of $3.2

billion and a net loss of $23.6 million

for 2018.

Total gold output fell roughly 8% to

the lowest level since 2010.

AISC fell 1% yoy, to $965/oz, which was down roughly 3% from the average for the company for the preceding half-decade. The average price received per oz for 2018 was $8 more than it was for 2017, making it the highest it has been since 2013. It was also roughly the average for the company for the preceding half-decade, and roughly $20 above the average for the 2007-2017 timeframe. The difference between price received and AISC was $303.

Kinross Gold mined roughly 15% more ore yoy, hitting the average for the company for the preceding five years of about 130 million mt. In 2018, the company reported record annual production at a couple of its mines, including Paracatu (Brazil), which produced roughly 523,000 oz. Kupal (Russia) produced roughly 490,000 oz. The miner logged roughly $1 billion in capital expenditures for the year, up yoy due to increased spending at Round Mountain (Nevada), Bald Mountain (Nevada) and Tasiast (Mauritania).

In 2019, Kinross plans to commission a processing circuit at Bald Mountain, commence stripping at the Fort Knox Gilmore project (Alaska, USA), complete a feasibility study for the La Coipa Restart project (Chile), and further evaluate the Tasiast Phase Two expansion project. The company reports it expects to spend roughly $1 billion on capex next year.

No.5 Polyus (2.44M oz)

Russia’s Polyus reported an adjusted net

profit of $1.3 billion, up more than $300

million yoy. It reported total revenue rose

7% yoy to $2.9 billion. Net debt was

roughly the same yoy at $3 billion.

Total gold output increased 13% yoy to the highest level yet for the mine. This was in part due to a 12% yoy increase in output from Olimpiada. Almost 50% more ore was mined and about 7% more ore was processed at the mine. Output for the year rose yoy at four of the company’s five producing mine sites. AISC fell by roughly 1%, and was 16% below the average for the company for the preceding five years. Polyus ranked first among the top miners for lowest AISC. Average realized price rose $6 yoy, but was 2% below the average of the company for the preceding five years. The difference between realized price and AISC was $660, easily the highest for the miners E&MJ researched.

In 2018, the company logged $736 in capital expenditures. Roughly $182 million of that went to Olimpiada, which ordered new haul trucks and plant circuit solutions. The company reported spending more than $100 million last year on IT infrastructure improvement projects and enterprise resource planning.

In 2019, the company plans to invest roughly $725 million “across the business,” Polyus reported. Big equipment purchases and infrastructure projects were reported to be under way at three mines at the close of 2018.

No.6 Newcrest Mining (2.42M oz)

For the last half of 2018, Australia’s

Newcrest Mining reported a net profit of

$237 million. For the year that ended in

June 2018, it reported a “statutory” profit

of $202 million. The company by many

measures had a banner or even breakout

2018. For example, it is the only company

E&MJ looked at that managed a trifecta:

increased production, lowered AISC, and

increased the average realized price yoy.

In 2018, total gold output rose 6% yoy, to just above the average for the company for the preceding half-decade. The company mined 17% more ore, and processed roughly 3% more ore yoy. Both numbers were above the averages for the company for the preceding five years. Lihir, the company’s flagship mine, and the third biggest mine in the world, moved 33 million mt of ore to produce 975,571 oz gold, a 6% increase yoy.

In 2018, AISC fell 7%, to $780/ oz, roughly 6% below the average for the company for the preceding half-decade. Of the companies E&MJ tracks for this article, Newcrest ranked second for lowest AISC. Average realized price for the year was up $2 yoy and was 2% higher than the average for the company for the preceding half decade. Newcrest ranked second for highest realized price in 2018. The difference between price received and AISC was $494, also ranking second.

During 2018, the company acquired a stake in Lundin Gold, released studies on two big projects, and a resource estimation on a third. For the six months ending in December 2018, the company logged non-sustaining capital expenditures of $74 million.

The company expects non-sustaining capital expenditures of as much as $235 million for the year ending in June 2019. It expects to produce 2.5Moz for the same timeframe. Newcrest reported estimated gold ore reserves of roughly 54Moz as of the end of December 2018.

No.7 Goldcorp (2.3M oz)

Goldcorp reported net earnings of $63

million for 2018, down from $360 million

in 2017. The company reported a net

loss for the year of more than $4 billion,

and adjusted net debt rose by 20% yoy.

AISC rose by 3% yoy, but it was roughly 7% lower than the average for the company for the five preceding years. The average realized price rose by $4 yoy and was right at the average for the company for the five preceding years. The difference between price received and AISC was $419.

In 2018, the Peñasquito’s Pyrite Leach Project achieved first gold in November and commercial production in December. Borden (Ontario, Canada) and Coffee (Yukon, Canada) projects both moved forward with permitting, and NuevaUnión (Chile) completed a prefeasibility study. The company logged $1.2 billion in “expenditures on mining interests” for the year.

For 2019, the company’s acquisition by Newmont is calendared to close in Q2. Lower grade will impact numbers from three of the company’s seven producing mines. However, production numbers could rise yoy as grade improves at Peñasquito, Goldcorp reported. Musselwhite’s Materials and Handling project (Ontario, Canada) and Borden are expected to achieve commercial production in H2. The miner reported $301 million in “capital expenditure commitments” for 2019.

Goldcorp reported it expects to produce between 2.2 million and 2.4 million oz in 2019 at an AISC between $750 and $850/oz. Mineral reserves as of June 30, 2018, were 52.8 million oz.

No.8 Gold Fields (2M oz)

South Africa’s Gold Fields Ltd. reported

headline earnings for 2018 of $60.6 million,

down from $209.9 million in 2017.

The “normalized profit” came to $26.9

million, down from more than $153 million

the year prior. Net debt was logged at $1.6

billion for the year, up roughly 24% yoy.

Total gold output fell roughly 6%, to the lowest level since 2013, and was down 5% from the average for the company for the five preceding years. The company milled roughly the same amount of ore in 2018 as it did in 2017.

The company labeled 2018 as “the peak year of capital spent on new projects.” The company logged $814 million, of which $334 million was filed as “mine cash flow,” which includes “project capital.” In 2018, AISC rose roughly 3% yoy to the highest level since 2015. It was down 6% from the average for the company for the five preceding years. The average price received fell $4 yoy to hit what essentially is the average for the company for the previous five years. The difference between price received and AISC was $270, the lowest for the miners reviewed by E&MJ.

Last year, the company bought into the Asanko project (Ghana). In March 2018, it entered a 50/50 joint venture with Asanko Gold and acquired a 90% interest in the namesake mine, which produced 223,000 oz in 2018. The company reported it plans capital expenditures reaching $633 million in 2019. Gruyere (Australia) will ramp up production starting in Q1, with first gold calendared for Q2. Asanko’s production will contribute to the company’s numbers this year as well. Damang is expected to mine higher grade ore starting in H1.

The company reports it expects to produce between 2.13 million and 2.18 million oz at an AISC of between $980 and $995/oz. Gold Fields reported that at year-end, it had 50.3 million oz of attributable gold reserves.

No.9 Agnico Eagle (1.6M oz)

Headquartered in Ontario, Canada, Agnico

Eagle Mines Ltd. reported a net loss

of $326.7 million for 2018. For the year

prior, it reported a net income of $240

million. In 2018, the company increased

its long-term debt by 25% yoy.

Total gold output in 2018 fell roughly 5% yoy to the lowest point since 2014, but was up about 8% over the average for the company for the five preceding years. Production fell by a whopping 29% at Meadowbank (Canada), slightly to 344,000 oz at La Ronde (Canada), and at Lapa (Canada), Kittila (Finland), and Creston Mascota (Mexico). Meadowbank is transitioning out of full production, the company reported. Production rose by 10% to 350,000 oz at Canadian Malarctic, slightly at Pinos Altos (Mexico) and La India (Mexico), and at Goldex (Canada). LaRonde Zone 5 mine, basically an expansion project targeting some 225,000 oz in mineral reserves, came online in 2018 and contributed 18,620 oz to the company’s total gold output.

The miner milled roughly 2% less ore yoy. AISC was up about 9% yoy to the highest point since 2014. It was up only slightly over the average for the company for the preceding five years. The average realized price received per oz was up $5 yoy and was $7 above the average for the company for the preceding five years. The difference between price and AISC was $389.

Agnico Eagle reported it will produce 1.8 million oz in 2019. “We anticipate record gold production in 2019,” the company reported. At December 31, 2018, the company’s gold reserves were reportedly 22 million oz.

No.10 Harmony Gold (1.4M oz)

Harmony reported increasing revenues and

a profit of $5 million to close out 2018.

The big news for the miner was a big uptick

in gold production, as it outproduced

Yamana Gold, Randgold and Sibanye-Stillwater

for the first time since 2013.

Gold production increased 30% yoy. Harmony also processed 31% more ore in 2019. The company attributed the uptick to “inclusion of Moab Khotsong (South Africa) and Hidden Valley (Papau New Guinea)” in its asset portfolio. The former produced 142,042 oz for the six months that ended December 31, 2018. Hidden Valley produced 100,021 oz in the same time period. During that timeframe, total gold output increased at seven of 11 other projects.

In 2018, AISC rose 4% yoy, to $1,234/oz, roughly the average for the company for the preceding half decade, but also the highest it has been since 2013, when it almost reached $1,500/ oz. The average price received for 2018 rose almost 3% yoy, to $1,338, which was 1% above the average for the company for the preceding half-decade, and the highest it has been since 2013, when it crested $1,603. Harmony ranked first for highest average received price in 2018. The difference between price received and AISC was, however, a paltry $105/oz. The company reported it expects to produce 1.5 million oz in 2019.

It stated in a 12-month report released last summer that its mineral reserves were 36.9 million oz.

Randgold (1.3M oz)

According to Barrick, Randgold’s “profit”

for 2018 was roughly $227 million. It reported

revenues for the year of more than

$1.1 billion. “Randgold had no outstanding

debt,” Barrick reported.

The information available for the company

for the year was limited to what Barrick

reported.

At the mines for which 2018 data was available, the miner, in general, moved and processed less ore. Total gold output fell more than 2% yoy, but was up roughly 10% over the average for the company for the preceding five years. Average price received per oz was up $8 yoy, according to Barrick, to the highest point since 2013. It was $9 above the average for the company for the preceding half-decade.

Barrick bought a couple of world-class mines when it acquired Randgold. Loulo- Gounkoto (Mali) produced 660,000 oz in 2018; Tongon (Côte d’Ivoire) produced 230,000 oz; and Kibali produced 363,000 oz. At the end of 2018, Randgold had roughly 12.8 million oz in proven and probable reserves, according to Barrick.

Sibanye-Stillwater (1.2M oz)

South Africa’s Sibanye-Stillwater reported

“headline” losses of $1.3 million for 2018.

While the company processed 43%

more ore, total gold output plummeted

16% yoy, due to various disruptions, the

company reported. Among other things,

infrastructure repairs, a strike and a power

outage jibed with the closing of a mine

to tank production numbers in the midst

of rising costs and relatively flat prices.

AISC rose 16% yoy to $1,309/oz, the highest on record for the company and the highest for the year for the gold miners E&MJ tracks. The company offers information on AISC on its site going back to 2013. The spike was related to “the significant fixed overhead cost component for South African gold operations.” The average realized price per oz rose $5 yoy to the the highest it has been since 2014, and $7 below the average for the company for the preceding five years. The difference between AISC and the price received in 2018 was $50, the lowest for the gold miners E&MJ tracks.

In July, the deal closed wherein the miner exchanged certain assets for a 38% stake in DRDGold, described as a midtier gold miner with 3.82 million oz in reserves. That bumped up total gold output for Sibanye by more than 60,000 oz on the year. The company reported mineral reserves of 16.6 million oz, as of December 31, 2018. It declined to report guidance numbers until the resolution of the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union strike, which was moving through the courts as of this writing, is resolved and reported.

2019 Guidance

The price of gold dipped hard in 2018 as

the Federal Reserve made key rate hikes

totaling 100 basis points over the course

of the year and as the other major central

banks of the world made hawkish moves

and sounds. Alongside copper prices and

stocks worldwide, gold briefly appeared to

be on the brink of entering a bear market.

It then moved upward slightly in Q4.

Key rates set by the central banks of the world are not the only factors driving gold price. They are simply the biggest. Other factors include “the sale or purchase of gold by central banks and financial institutions, exchange rates, inflation or deflation, (all three of which are central bank policy-driven,) global and regional supply and demand, and the political and economic conditions of major gold-producing and gold-consuming countries throughout the world,” Goldcorp reported. “A steady tightening of U.S. monetary policy provided the backdrop for gold price movement in 2018, with the U.S. Federal Reserve raising benchmark interest rates four times during the year, for a total of nine such increases since the current cycle began three years ago.”

The price of gold is not the only factor driving production efforts at the world’s largest mines. But it is the biggest. Newmont reports that “decreases in the market price of gold and copper can also significantly affect the value of our product inventory, stockpiles and leach pads, and it may be necessary to record a write-down to the net realizable value.” Polyus made a similar admission. “The group’s results are significantly affected by movements in the price of gold and currency exchange rates, principally the rubble to dollar rate,” it reported. “The market price of gold is a significant factor that influences the group’s profitability and operating cash flow generation.”

Therefore, one likely reason gold production tanked as hard as it did in 2018 is the major companies all anticipated the key rate hikes and the impact on price and paced their production efforts accordingly. This year will bring more of the same in the sense that corporate officers will try to predict key rate decisions by the central banks and will set plans accordingly. “As 2019 gets under way, gold prices are holding on to recent gains helped by a softer U.S. dollar and reports of several central banks around the world increasing their gold reserves,” Goldcorp reported. “Most notably, China recently announced an increase in gold reserves during December 2018 marking their first reported increase in over two years.” Russia lately has been in the news for central bank purchases of gold as the country, and a handful of others, seek to de-dollarize. “Any continuation of official sector purchases is expected to help to provide support for the precious metal; and while interest rate policy in the U.S. will continue to play a major role in gold’s fortunes over the year ahead, an increasing number of financial market commentators are questioning the speed with which rates have been increased throughout this cycle, leading to calls for a pause in the process,” it said.

Dovish central bankers could assure continued lowish rates, which will guarantee the flow of liquidity in global markets and provide at least gold price stability for much of 2019. If the global economy turns downward symmetrically, as some, including the International Monetary Fund, are warning it could, and as copper prices and the U.S. Treasury yield curve have repeatedly suggested it could, the central banks of the world would likely, in unison, cut rates to further stoke liquidity, since that worked so well a decade ago. The one-two punch of lowered rates amid the fear prompted by a global economic downturn would be a boon for gold as a safe-haven asset. Conversely, a stronger and rising dollar resulting from tighter liquidity amid generally upbeat economic news would be bearish for gold prices.

1 - Excluded from this article are, among others, pure play gold producers that did not release in time reports providing key data. Companies that could qualify as top producers but were excluded from this analysis include, but are not limited to, Zijin Mining Group Co. Ltd. and Navoi Mining and Metallurgy Combinat.