CSR Earns a Seat at the

Boardroom Table

Tighter external scrutiny, expanding internal initiatives and rising penalties for

noncompliance are pushing corporate social responsibility considerations into a

more prominent position

By Russell A. Carter, Contributing Editor

Perhaps one of the most unexpected findings — at least, perhaps, to an outside industry observer — to emerge from the survey is that mining companies are high on the list of major industrial sectors that recognize the validity of human rights. Just under nine out of 10 (88%) mining respondents reported that they consider human rights to be a legitimate business issue. This level of acknowledgement compares with other resource-oriented industrial categories such as Oil & Gas (77%), Construction & Materials (71%) and Forestry & Paper (70%). However, mining’s high ranking on human rights concerns in the latest report isn’t just a statistical aberration, it has consistently scored strongly in similar KPMG surveys in the recent past.

“This high rate (for mining) might be expected given that mining companies rely on good relationships with local communities in order to operate their mining assets successfully over long periods,” noted the study’s authors. “Reporting on human rights performance can be an essential part of maintaining social license-to-operate for these businesses.”

What the authors didn’t note, however, is that while there is no lack of guidelines, checklists, analytical approaches and consultation services aimed at assisting mining companies in the formulation and execution of human rights-related CSR initiatives, there also is no guarantee that any initiative of that type will achieve expected results — or that it won’t backfire and become a financial, social or public-relations albatross. A complex combination of local, regional and national governance policies, along with corporate ignorance or inattention to local cultural peculiarities and land-access customs, the rising power of social media networking and resource nationalism can transform CSR into a Rubik’s Cube-style exercise where getting all the colored blocks into the correct position still might not produce a clear-cut win.

Another of the KPMG survey’s findings highlights the changing nature of CSR reporting; statistics count less than outcome. Companies have been eager to report numbers — volume of water saved or tons of CO2 emissions reduced by conservation efforts, for example — but financial stakeholders now want to know the specific context of those numbers and whether they have a directly translatable impact on society or business performance.

Meanwhile, mining companies are increasingly interested in finding CSR and sustainability solutions that offer prospects of maintaining or boosting corporate revenue while benefiting society. And, as the Internet of Things expands and data management, telecommunications and remote-sensor technologies improve, miners are increasingly inclined to turn to tech for solutions that can be used to reduce or control the physical impact on the areas in which they operate. In this article, E&MJ offers a glimpse of examples in each of these avenues of opportunity.

Heed the Human Factor

The KPMG survey’s finding that mining companies generally recognize

human rights as a valid business issue can be viewed as

an indication that the industry is heading down the right path,

but a recent article written by two attorneys well-versed in international

corporate and human-rights issues explains how that

path might just get tougher instead of easier.

Viren Mascarenhas and Kayla Green at global law firm King & Spalding maintain that companies operating in the extractives industry will increasingly come under scrutiny by the human rights community, as well as their employees, clients, and their shareholders. Mascarenhas is a member of the law firm’s International Arbitration Practice Group and holds several leadership roles within the American Bar Association Section of International Law. Green works on matters including white collar criminal litigation and Foreign Corrupt Practices Act matters. She also works on a pro bono basis on civil and human rights matters, and assists clients with immigration and refugee visas.

According to them, mining companies face unique and mounting challenges with regard to human rights concerns. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has issued three editions of the OECD Guidance, which provide guidance to mining companies regarding the sourcing of conflict minerals. National Contact Points (NCPs), established in OECD member states to provide guidance and handle inquiries related to the OECD Guidelines, increasingly are investigating complaints filed by local communities regarding mining operations. National laws increasingly impose human rights reporting requirements on companies in the extractives industry. For example, European Union (EU) legislation on regulating conflict minerals on trade in tin, tantalum, tungsten and gold will come into effect in 2021. And, recent developments in jurisdictions such as Canada and the United States indicate that parent companies may well be held accountable by their national courts for the actions of their subsidiaries operating overseas that violate human rights norms.

Furthermore, the authors state, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and investors have also sought to identify best practices regarding a mining company’s compliance with human rights norms by comparing the performance of mining companies against each other. Recently, a consortium of organizations conducted the Corporate Human Rights Benchmark (CHRB), which sought to rank the top 100 companies in the agricultural products, apparel, and extractive industries on their human rights performance. As part of this initiative, the CHRB evaluated 41 extractive companies on their human rights policies, human rights due diligence, and their responses to allegations of human rights violations (including remedies). The overall average “score” awarded to the companies was 29.4%, with the highest scores being in the 60%-69% range. The study concluded that the areas in which these companies were lacking the most was showing a true respect for human rights, and undertaking sufficient human rights due diligence into areas of their business susceptible to human rights violations.

The consortium (www.corporatebenchmark.org} behind the benchmark study includes several socially responsible investment (SRI) financial asset management companies, a human rights NGO, a think tank, and a large Nordic private bank, with assistance from a trio of business-intelligence and human-rights research and data aggregators.

Given this rising level of scrutiny, said Mascarenhas and Green, mining companies in particular need to (a) develop a human rights policy; (b) create a culture of respect for human rights through systematic training and other initiatives; (c) conduct due diligence to identify areas of potential human rights violations given the needs and nature of the business; (d) report on human rights practices (required under various reporting laws); and (e) provide a remediation process, such as a grievance mechanism, to remedy human rights violations.

For the mining industry, the stakes are high and potential penalties stemming from poor planning, inattention or noncompliance can be severe. “The international and national legal framework governing the compliance of businesses with human rights is rapidly evolving,” explained the authors. “Companies operating in the extractives industry face special risks. In addition to issues regarding the sourcing of minerals from conflict areas, there is significant environmental and social opposition to mines operating all over the world. Responsible companies must comply with human rights norms. Failure to do so may have significant adverse consequences, including potential high-stakes litigation that can bankrupt companies.”

Turning to Tech Tools

The application of technological tools is an expanding and

somewhat less unpredictable avenue for mining companies to

monitor their impact on society and the environment as part of

an overall CSR effort.

In its most recent CSR report, Barrick Gold said it is “… finding more ways to leverage digital technology to bring our operations and our host communities closer together.” At the environmentally controversial Pascua-Lama project, located on the border of Chile and Argentina and currently being advanced by the company toward a prefeasibility study, Barrick said it now publicly shares real-time water monitoring data from the nearby Estrecho river. In the future, said Barrick, it intends to make other real-time performance metrics publicly available, along with virtual site tours.

Newmont Mining reported that, to address deficiencies in cyanide testing, it led efforts — as part of an International Standards Organization (ISO) working group — to develop a gas-diffusion testing method that allows for real-time measurement of cyanide and has been found to improve the accuracy of the tests. Newmont said that at the 2016 ISO meeting, the results of a global interlaboratory study on the gas-diffusion method were reviewed and unanimously accepted. The method was advanced for acceptance as an ISO standard. To perform the gas-diffusion testing method at its sites, the company developed an online analytical tool that has been deployed at five operations with further installations planned. It also is benchmarking the range of testing methods it uses across its sites to ensure best practices are being used.

The potential applications of Internet of Things (IoT) technology continues to draw interest within the industry. A survey released earlier this by mobile satellite communications provider Inmarsat, titled The Future of IoT in Enterprise - 2017, found that 57% of respondents from the mining sector reported that “the most exciting innovation” that IoT will bring to the world is improved environmental monitoring.

Joe Carr, director of mining at Inmarsat Enterprise, commented, “Improving environmental monitoring is an area where mining operators clearly see real value in IoT. The increasing pressure from strict government regulations focused on mining’s environmental impact is placing a heavy burden on businesses in the sector, so operators must embrace innovative technologies if they are to comply and continue to operate efficiently and sustainably.”

Mining businesses have a duty of care over the lifetime of a mine to ensure that they minimize their impact on the environment and rehabilitate the land to its natural state. When this is done by manual processes, it can be expensive and prone to error, with suboptimal data collection and analysis. Inmarsat said it is currently working with several mining operators to achieve their CSR objectives and comply with government regulations by deploying innovative monitoring solutions made up of connected networks of sensors and devices.

These digital networks are able to deliver accurate, real- time insight and intelligence on a wide variety of data points to a cloud-based platform for analysis. For example, a network of sensors across a tailings dam can constantly gather data on the levels and integrity of the dam, avoiding the expense of sending a staff member out to gather a single data point and removing the possibility of human error, while enabling staff to react instantly if readings breach minimum or maximum safety levels.

CSR Continues Beyond Closure

The typical CSR chain of concerns doesn’t end with the shutdown

or closure of a mine site. Whether a company plans to

maintain the site for possible restart or has no intention of mining

there again, certain responsibilities arise — along with opportunities

to create CSR-positive relationships and outcomes.

For example, De Beers Canada recently announced a new

partnership for extended care and maintenance services at its

Snap Lake mine with Det’on Cho Corp. (DCC), the business development

arm of the Yellowknives Dene First Nation. Snap Lake

mine is located 220 kilometers (km) northeast of Yellowknife,

Northwest Territories (NWT). The mine opened in 2008 and was

placed on care and maintenance in December 2015.

The three-year contract with an option for extension commits DCC to provide ongoing care and maintenance services at Snap Lake, working alongside De Beers Canada staff. Under terms of the contract, DCC will furnish personnel for site safety, camp support, travel and logistics, environmental monitoring, and management services while the mine is in extended care and maintenance.

It is the fourth Tier 1 contract De Beers has awarded in the NWT over the past year as part of a focus on providing long-term benefits to Northern and Indigenous companies. De Beers also intends to shut its Victor mine in northern Ontario, Canada, after mining and production winds down in the first quarter of 2019. The subsequent demolition and environmental monitoring phase is expected to take three to five years. De Beers said it is working closely with community partners to create opportunities for employment and awarding contracts that will be required during this phase.

De Beers said progressive reclamation work has already been taking place at the mine for several years. To date, this has included the planting of several hundred thousand tree saplings and willow stakes that were harvested and grown locally through a community youth work program.

Kim Truter, CEO of De Beers Canada, said, “While we are focused on continuing to maintain production for the duration of operations, we are also planning responsibly for Victor mine’s closure in line with the agreed mine plan and our commitment to leaving a positive legacy.”

Occasionally, the ties that bind a mining company to CSR responsibilities and commitments at some deactivated sites can be tenuous — but expensive. Rio Tinto, for example, reported that company-wide, its legacy management team monitored and managed more than 100 old sites in five countries in 2016. In particular, it noted that after five years of construction, it is wrapping up major construction on the $500 million Holden Mine Cleanup Project, with final construction ongoing in early 2017. The Holden project involves rehabilitation of a mine operated by a company that Rio Tinto never owned, along with construction of civil works and facilities that will add to the usefulness and quality of life for Holden Village’s residents and visitors.

The Holden site is located in a remote area near Lake Chelan in north-central Washington. It was one of the largest operating copper mines in the United States from 1938 to 1957. Developed by Howe Sound Co., the mine and related mill facilities produced about 200 million lb of copper, 40 million lb of zinc, 2 million oz of silver and 600,000 oz of gold from approximately 10 million tons of ore.

After the mine was closed, Howe Sound sold it and the accompanying town site to a religious organization for a token amount. A spiritual retreat center and community, known as Holden Village, has operated at the site since then, accommodating some 5,000 seasonal visitors a year. The remote village is accessible only via local ferry service on Lake Chelan or by hiking over the Cascade Mountains. It operates under a Forest Service special-use permit.

The environmental impact of tailings and waste rock dumped on wetlands and near the creek prompted the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to declare the closed mine a Superfund site in the late 1980s. EPA identified Intalco as the Potentially Responsible Party (PRP) for remediating the mine site. Intalco is a successor to Howe Sound, which operated the mine until it closed in 1960. Rio Tinto pointed out that it never owned or operated the Holden mine and that Intalco Aluminum Corp., a successor to Howe Sound, is responsible for the cleanup. However, through the 2007 acquisition of Alcan (formerly a part owner of Intalco), Rio Tinto agreed to pay for and manage the cleanup on behalf of Intalco. Intalco and Rio Tinto are separate companies.

The parties involved have been engaged in developing strategies and agreements for the mine remediation process since the mid-1990s. Some 14 different alternatives for the cleanup effort were studied. The U.S. Forest Service and other state and federal agencies signed off on the cleanup strategy in early 2012, and for the past five years, Rio Tinto said it’s had between 200 and 300 employees and contractors living in and working out of Holden Village. Over the life of the project, it has employed more than 1,800 people from the region.

Since starting work on the government-mandated cleanup in

2012, the company reported that it has:

• Re-shaped and re-contoured 9 million tons of tailings and

250,000 tons of waste rock piles;

• Sealed off the mine entrance;

• Built a water-collection system and underground barrier to

prevent further contamination;

• Demolished and buried the old mill building;

• Re-aligned 900 feet of Railroad Creek;

• Built a new barge ramp at Lucerne;

• Built a new parking lot at Chelan Boat Co. to allow staging;

• Built a new bridge to bypass Holden Village;

and

• Built and began operating a water treatment plant.

As construction work at the site winds down, Rio Tinto also has been planting thousands of trees in the area. The company said its latest economic impact study shows that the project has contributed nearly $240 million to Chelan and Douglas counties over the last six years. This includes wages paid to local employees, contractors, and equipment providers, as well as taxes paid to local and state governments. It also includes goods purchased from local businesses and revenue generated by individual salaries and expenditures within the local communities.

Leveraging the Value of Legacy Sites

Mineral producers interested in finding ways to cushion the economic

impact of inactive site maintenance and rehabilitation

on the bottom line may have a promising alternative in the form

of renewable energy production, according to a recent brief released

by the Rocky Mountain Institute, a nonprofit organization

focused on working with industry to develop cost-efficient renewable

energy initiatives.

Although interest in this option is expanding, potential opportunities

afforded by the approach may not be immediately

apparent to all mining executives, according to RMI. This could

occur because:

• Site supervisors and corporate officers simply may not be

aware of the possibility to develop renewables and/or storage

on legacy sites.

• Site supervisors and company executives may worry that renewables

development will require higher upfront capital costs

or will not be cost-effective in the long run.

• Mining executives may not have the expertise to screen their

portfolio of closed sites for optimal solar, wind and storage

assets.

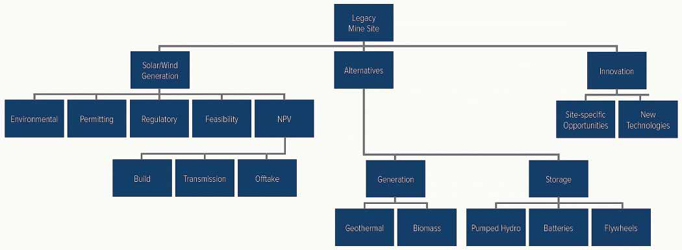

RMI maintains that renewable developments may not only be an appropriate alternative use for these sites, but they also have the potential to produce a sustainable revenue stream, thereby transforming these sites from liabilities into assets for the controlling company. For companies interested in taking advantage of this insight, RMI’s Sunshine for Mines team developed a methodology, illustrated in the chart, for screening legacy sites for renewable resource availability and when applicable, assessing the feasibility and value of their development. The end result is an overall scorecard of prioritized sites for development with their respective preferred technologies.

RMI said the Sunshine for Mines team can assesses the feasibility of solar/wind, alternative storage and generation, and innovative options for each site. Net present value (NPV) is assessed for solar/wind opportunities since costs are mature for these technologies. In the future, as costs become more standard, NPV may be assessed for alternative options as well.

Because legacy sites have a history of being operated as active mine sites, this can typically create conditions of soil contamination, maintenance requirements of tailings and waste areas, water management and mitigation requirements, and other operational liabilities. Moreover, the sites themselves may be subject to local, state, or federal regulations regarding land use and environmental impact. Before considering which technologies are optimal for a legacy site, the site must undergo an environmental, permitting and regulatory screening to ensure that renewable development is favorable. RMI’s examination criteria include permitting and land management (local, state, federal); natural, recreational, and scenic resources; land use, public services, and infrastructure; surface waters, floodplains, and wetlands; soils, geology, and groundwater; and threatened and endangered species.

RMI reported that it recently worked with BHP to evaluate the mining company’s North American portfolio of legacy sites for renewable development. Using the methodology described above, RMI identified significant potential for redevelopment and a subset of sites with a collective potential of more than 0.5 GW. For most of the sites, solar PV emerged as the largest opportunity, with a few being suited for wind development. Various storage technologies were also explored and, in some cases, recommended. The opportunities in the subset were ranked by overall value according to the variables assessed via the scorecard system. This helped BHP prioritize activities and take action on the most attractive opportunities.