The only diamond mine in Russia not in Alrosa’s portfolio, Grib was developed by

the oil-and-gas

The only diamond mine in Russia not in Alrosa’s portfolio, Grib was developed by

the oil-and-gas

company, Lukoil. Last November, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that

Archangel Diamond Corp.’s

15-year legal fight to win compensation from Lukoil for

what the company claimed was loss of its

contractual rights over Grib was at an

end. Archangel went bankrupt in 2010, having invested

US$30 million in the project

Since the last occasion when E&MJ took an in-depth look at

the world diamond industry, September 2011, the

world’s diamond producers have continued the process of restructuring

that began in the early 2000s when De Beers began

to relinquish its traditional role of industry custodian. In the

intervening period, statistics compiled by the Kimberley Process

Certification Scheme (KPCS) indicate that producers responded

in no mean way to reduced consumer demand, particularly in the

aftermath of the 2008 global economic

downturn, with output fluctuating within

a fairly narrow band between 2009

and 2015, and only showing signs of

picking up again last year.

Significant events within the industry

since 2011 have included De Beer’s

continued rationalization of its property

portfolio, reducing its interests in

South Africa and building new capacity

in Canada. And having spent a number

of years in evaluating the Bunder prospect

in India, Rio Tinto finally decided

that it was not viable and gave it away,

having also spent some $2.2 billion on

developing the underground section at

Argyle in Australia.

Winning the top spot in the producers’

league, Russia’s Alrosa clearly has

no intention of giving it up, and has

consolidated its position with new capacity

coming on stream. But perhaps

the most visible — and newsworthy —

aspect of the past six years has been the regular discovery of

large, high-value diamonds at mines run by a number of the new

generation of producers, companies that have both picked up

the discards from long-established producers such as De Beers,

and have explored, financed, developed and commissioned their

own new operations.

E&MJ’s 2011 article looked in depth at some of the background

to diamond resources, the history of production since

India ceased to be the world’s leading supplier of gem-quality

stones during the 1700s, and the world’s major diamond-mining

companies in the 21st century. In point of fact, little has

changed since then — the host rocks have remained the same,

the major producers have neither expanded nor contracted significantly, and history is history. There is thus little to gain by

repeating what was written then, and the interested reader is

directed to that article for information on those topics.

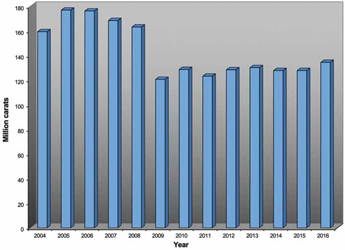

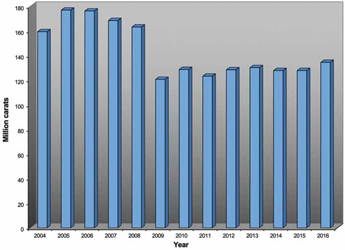

World rough diamond production, 2004-2016 (million ct). (Source: KPCS statistics)

World rough diamond production, 2004-2016 (million ct). (Source: KPCS statistics)

Recent Production Trends

Data compiled by the KPCS covering the period from 2004 to

2016 show clearly how the world diamond industry reacted to

the wider economic malaise that began in 2008. Before that,

consumer confidence was high, and demand for both industrial

and gem-quality diamonds was good.

As shown in Figure 1, the industry reached peak output of

176.7 million carats (ct) in 2005, albeit at an average value

of $65.68/ct. The drop in output in 2006, 2007 and 2008,

while noticeable, was minor in comparison to what happened in 2009,

when production plummeted to 120.2 million ct.

Since then, weak consumer demand

has effectively put a cap on what producers

are prepared to place on the market.

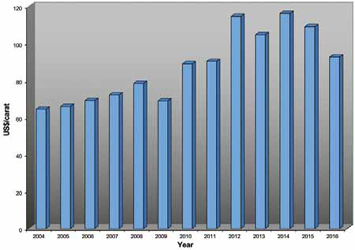

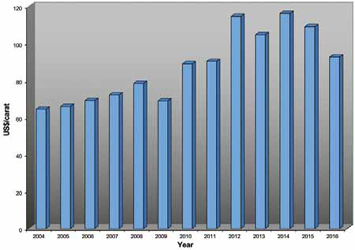

From time to time, as Figure 2 illustrates,

demand has squeezed the market somewhat,

to the extent that higher average

per-carat prices have given producers an

economic boost, although the marked increase

in output from 127.4 million ct in

2015 to 134.1 million ct in 2016 merely

managed to weaken average prices from

$108.96/ct to $92.49/ct as consumers

in China and India in particular were

wary of parting with their cash.

Bear in mind that these average

per-carat prices relate to rough (uncut)

stones, with a huge differential between

the amount paid for large, high-quality

gems and run-of-the-mill industrial

diamonds. This is clearly illustrated by

considering that the average price received

by producers in the DRC last year was $10.63/ct, while

their counterparts in Lesotho averaged $1,065.88/ct. KPCS

data show that the DRC produced 23.2 million ct of predominantly

industrial-quality diamonds. Lesotho’s 342,000 ct may

have been a small fraction of that, but the country’s mines

have developed a reputation for unearthing some truly spectacular

gemstones.

Average per-carat prices for world rough diamond production, 2004-2016 (US$/ct). (Source: KPCS statistics)

Average per-carat prices for world rough diamond production, 2004-2016 (US$/ct). (Source: KPCS statistics)

In addition, producers still have the capacity to manage their

diamond sales to a much greater extent than for most other

mined commodities. With the traditional method of sales based

around the concept of prepared packages of rough stones being

offered at “sights,” from the producer’s perspective the skill

comes in understanding what the market wants in relation to

consumer demand. Offloading surplus stock will inevitably result

in prices falling, yet for most producers there is a limit on

how much inventory they can afford to carry.

By way of illustration, Bain & Co. in the 2016 edition of its

Global Diamond Industry report for the Antwerp World Diamond

Center, noted that “Major rough-diamond producers in 2015 reacted

to the challenging circumstances of their customers by reducing

output, increasing their own inventory levels and providing

more flexible purchasing terms while cutting rough-diamond

prices. As a result, rough-diamond sales fell 24% in 2015.”

Published in the second half of the year, the report continued

“the industry rebounded in 2016. Restocking by midstream

players, following their inventory sell-off in late 2015, produced

growth of around 20% in rough-diamond sales during the first

half of 2016. However,” it warned, “strong rough-diamond sales in 2016 may again lead to swollen midstream inventories if retail

demand does not strengthen proportionately.”

Were these fears realized? According to De Beers in a report

published in June, global demand for diamond jewelry increased

marginally last year to reach a total of $80 billion, with the U.S.

alone accounting for $41 billion of this. Elsewhere in the world,

the Japanese and Chinese markets also showed growth, while

jewelry demand in India and the Middle East was weaker.

Gahcho Kué, where the De Beers-Mountain Province Diamonds joint venture began mining mid-last year, is expected to produce some 54 million ct over an initial 13-year life.

Gahcho Kué, where the De Beers-Mountain Province Diamonds joint venture began mining mid-last year, is expected to produce some 54 million ct over an initial 13-year life.

Commenting on these data De Beers’ CEO, Bruce Cleaver

said “while U.S. demand drove global growth in 2016, it is increasing

demand from emerging markets that is behind the last

five years being the strongest on record. Despite some markets

facing challenging conditions last year, we see this trend continuing,

with improvements in demand from China and India, in

particular, emerging in 2017.”

Conflict Diamonds: Still a Challenge

As E&MJ noted in its 2011 article, established in 2003, the

Kimberly Process (KP) “relies on a system of cross-referencing

production, exports, and imports of rough diamonds between producer

and consumer countries. The aim is to make it more difficult for illegally mined or smuggled diamonds to be sold to help

finance civil conflicts.” The article went on to highlight some of

the weaknesses that have been perceived in the way that the KP

operates, in particular its inability to police areas where diamond

production takes place under conflict or corrupt conditions.

Consisting of 54 participating countries and organizations,

the KP claims that 99.8% of world diamond production now

comes from conflict-free sources. Without question, it has made

major inroads into this source of income for the participants in

(usually) civil wars, but has it now been able to achieve the level

of credibility that it needs to win public confidence?

Set up to strangle the trade in conflict diamonds, the Kimberly Process suspends export

certification

Set up to strangle the trade in conflict diamonds, the Kimberly Process suspends export

certification

for the Central African Republic between 2013 and 2015. The organization

has since allowed exports

to resume from areas under government control, but critics

question the effectiveness of the way this

is policed. (Photo: Emmanuel Braun, Reuters)

That corruption can ease the way for diamonds to be awarded

fraudulent KP certification is one allegation frequently made

by its critics. An article in the U.K. newspaper, The Guardian,

in 2014 summarized other concerns. “The process has

two main flaws,” said author David Rhode. “First, its narrow

terms of certification focus solely on the mining and distribution

of conflict diamonds, meaning that broader issues are

not addressed.

“Second, a KP certificate does not apply to an individual

stone but to a batch of rough diamonds, which are then cut and

shipped around the world. Without a tracking system, this is

where the trail ends,” he added.

In fairness, the message seems to have landed on fertile

ground, with the chairman of the KP in 2016, the UAE’s Ahmed

Bin Sulayem, taking the unprecedented step of publishing a

“midterm” report on progress being made during his tenure of

the office. “Only by visiting diamond-producing countries is it

possible to fully appreciate the challenges affecting all those

involved in diamond production, from government regulators

to hundreds of thousands of miners and their families whose

livelihood depends on a transparent, accountable industry,” Bin

Sulayem said. “This work will continue.”

One of the key innovations proposed for the KP during

2016 is the establishment of a blockchain system for tracking

diamonds. Bin Sulayem’s report explained that “blockchain is

a list of transactions that happen in a peer-to-peer network.

Those who join in the blockchain can transfer value without

the need for a central third party or ‘clearer’ like a bank.

Blockchain is a distributed database, completely aligned to

the structures of the internet, which maintains a continuously

growing list of encrypted data records, secure from tampering

or revision.”

The report went on to acknowledge that “adopting blockchain

technology would be a long process requiring a great deal

of research. The cost and complexity of implementation would

also be significant,” it added. But by establishing a permanent

public record of the diamonds in the blockchain, this would create

an indisputable, unchangeable chain of ownership transfer,

replacing physical certificates with digital proof of a diamond’s

progress from mine to madame.

Russian Roundup

With an output of more than 40 million ct last year, Russia accounted

for nearly 30% of the world’s total rough diamond production,

and well ahead of the second-largest producer in volume

terms, the DRC (23.2 million ct). The other big producers, Botswana,

Australia, Canada, Angola and South Africa produced 20.5,

13.9, 13, 9 and 8.3 million ct, respectively, KPCS data show.

In its 2016 annual report, Alrosa, which

celebrates its 60th anniversary this year, reported

group production of 37.4 million

ct of rough diamonds, with sales revenues

41% higher than in 2015 at RUB317.1

billion ($4.9 billion). A key event during

the year was the reduction in the federal

state holding by a further 10.9%, bringing

it down to 33%. This followed a 16% selloff

in 2013, with the prospect of the state

selling a further 8% stake either this year

or next being mooted. However, while last

year’s sale realized $814 for a federal government

that is desperate to plug holes in

its finances, this was some $90 million less

than it had hoped for, with the Financial

Times reporting at the time that “investor

appetite was affected by poor political relations

between Russia and the West.”

In June, Debmarine Namibia’s US$157 million SS Nujoma was named at a ceremony at Walvis Bay. The company

says

In June, Debmarine Namibia’s US$157 million SS Nujoma was named at a ceremony at Walvis Bay. The company

says

that it is the world’s largest and most advanced diamond exploration and sampling vessel. (Photo: De Beers)

On the operational side, Alrosa reported that the underground

section of its Mir mine reached its design capacity of 1 million

metric tons per year (mt/y) in 2016, and that it is starting the development

of the Zarya pipe. In addition, it began construction of the

infrastructure for the Verkhne-Munskoye deposit, with capex costs

to bring a mine into production cited at RUB63 billion ($1 billion).

While most of Alrosa’s operations are in Russia’s Far East, its

Severalmaz subsidiary has been developing the Lomonosov deposit

in the Arkangelsk district of northwest Russia. Two of the six

pipes that occur there (Arkhangelskaya and Karpinskogo-1) are in

production, with the capacity of the ore processing plant having

been increased from 1 million mt/y to 4 million mt/y in 2014.

The district is also host to the Verkhotinskoye (Grib) mine, operated

by Russia’s only other diamond producer, Arkhangelskgeoldobycha

— until earlier this year a subsidiary of the oil-and-gas company,

Lukoil, and now owned by the Otkritie Holding group. Having earned

US$314 million from rough diamond sales from Grib in 2016, Lukoil

sold the operation to Otkritie for US$1.45 billion in March.

“Lukoil successfully developed a major diamond project

from its very early stage and brought the Grib diamond

mine to almost full capacity on time and within budget.

Spinning-off of this noncore asset allows us to effectively

monetize the significant shareholder value that we have

created over the past five years,” explained Alexander Matytsyn,

Lukoil’s senior vice president for finance. The mine produced

around 4.5 million ct last year, having come on stream in

2014, and is reported to be the eighth-largest diamond operation

in the world.

Canada’s Diamond Sector Expands

Since Ekati was commissioned in 1998, Canada’s diamond

industry has grown to the extent that the country is now the

world’s fourth-largest producer. Ekati was followed by Diavik

in 2003, Jericho in 2006, and by Snap Lake and Victor in

2008. The commissioning of Renard and Gahcho Kué early

this year followed a period of consolidation within the sector.

The 1,109-ct ‘Lesedi La Rona,’ the second-largest

The 1,109-ct ‘Lesedi La Rona,’ the second-largest

gem-quality rough diamond ever

discovered, according

to Lucara Diamond Corp. At auction last year, the

bidding

stopped at US$61 million, below the

company’s reserve price.

However, it has by no means been plain sailing for the industry,

with Jericho — Nunavut’s only diamond mine — closed as

uneconomic in 2008 and Snap Lake falling foul of high pumping

and water-treatment costs in 2015. Following this, De Beers

sought offers for the property, but having failed to do so, announced

in December that it planned to flood the mine. Snap Lake

produced 1.2 million ct in 2015, and at the time had resources to

support production until the late 2020s.

De Beers also faces challenges at its 600,000-ct/y Victor

mine in northern Ontario, where reserves in the existing

pit are expected to be exhausted by late 2018. Earlier this year

Reuters reported that the company had shelved plans to evaluate

the neighboring Tango resource, following its inability to reach

an agreement on the project with the Attawapiskat First Nation.

De Beers presumably hopes for better fortunes with its third

Canadian mine, Gahcho Kué, where it is in 51:49% joint venture with Mountain Province Diamonds. Operations at the

three-pit complex started to ramp up in August last year, with

commercial production being confirmed in early March.

Located some 280 km northeast of Yellowknife in the Northwest

Territories, Gahcho Kué operates on a fly-in/fly-out basis.

The world’s largest new diamond mine, it is based on a cluster

of four diamond-bearing kimberlites, three of which have a

probable mineral reserve of 35.4 million mt grading 1.57 ct/mt.

Commissioned at a capital cost of near $1 billion, the mine is

expected to produce an average of 4.5 million ct/y, with a 13-

year lifetime output of around 54 million ct.

Mountain Province Diamonds discovered the 5034 kimberlite

pipe at Gahcho Kué in 1995, with De Beers then adding

to the resource with the discovery of the other three pipes.

Mining is now focused on the 5034, Hearne and Tuzo pipes,

requiring the water level in the adjoining Kennady Lake to be

lowered and protective dykes and berms constructed to allow

access to them.

In all, De Beers produced just over 1 million ct from its Canadian

operations last year, markedly down from the 1.9 million ct

it won in 2015 — mainly as a result of Snap Lake having been

suspended at the end of 2015.

Meanwhile, Stornoway Diamond Corp. sneaked in ahead

of Gahcho Kué with the declaration of commercial production

at its Renard mine at the beginning of January. Situated 350

km north of Chibougamau in the James Bay region of northcentral

Québec, Renard cost Stornoway, the sole owner, C$775

million to develop.

Ore processing began in July 2016, two years after construction

began. The mine produced 2 million mt of open-pit ore

during the year, while recovering nearly 450,000 ct.

Four kimberlite pipes host the initial resource of 22.3 million

ct. Open-pit mining from the combined Renard 2 and 3 pipes will

continue until next year, and from the Renard 65 pipe until 2029.

Underground production will be from the Renard 2, 3 and 4 pipes,

with Renard 2 holding the bulk of the underground resources. Stornoway

expects to produce 1.7 million ct this year, while mining 4.4

million mt from the open pits and 500,000 mt from underground.

And the search for Canadian diamonds is by far from over,

with a number of junior companies at work. These include Peregrine

Diamonds with its Chidliak open-pit project on Baffin Island,

Dunnedin Ventures (the Kahuna project in Nunavut) and

Kennady Diamonds, which has the Kennady North landholding

near Gahcho Kué.

In June, Rio Tinto took a three-year exploration option on

Shore Gold’s long-standing Star-Orion South project in the

Fort à la Corne area of central Saskatchewan, with a $18.5

million commitment to win a 60% stake in a future joint venture. Conversely, De Beers recently

walked away from its own seven-year,

US$15.8 million option agreement with

CanAlaska Uranium in the West Athabasca

region of the province, having failed to

identify any kimberlite at targets identified

from airborne magnetic surveys.

Exploration core drilling is just one end-use for industrial diamonds. Natural stones, while comprising

Exploration core drilling is just one end-use for industrial diamonds. Natural stones, while comprising

around 70%

of production, now account for only 1% of annual industrial diamond demand, with China by

far the world’s biggest

producer of synthetics. (Atlas Copco bits on the left and Roschen NQ wireline core

bits on the right.)

And in July, Dominion Diamond Corp.

(formerly Harry Winston Diamond Corp.,

formerly Aber Diamond Corp.), which has

a 40% stake in Diavik with Rio Tinto and

owns 80% of Ekati, agreed to a US$1.2

billion takeover by privately owned, U.S.-

based The Washington Cos. The new owners

have said they plan to invest in the Jay

and Fox Deep projects at Ekati, and in new

greenfield exploration.

Crystal Gazing

In the most recent edition of its diamond industry report, Bain

& Co. suggested that in value terms, measured in constant dollars,

global demand is likely to grow at a rate of between 2%

and 5% annually in the period up to 2030. Against that, the

company believes that “the global supply of rough diamonds will

decline by an average of 1% to 2% per year from 2016 to 2030

because of the aging and depletion of existing mines.”

This decline will be offset to a certain extent by new mines

coming on stream which, the report suggested, could add as

much as 26 million ct/y up to 2026, then tail off to around 16

million ct/y after that. All in all, plans announced by producers

indicate an increase of rough diamond production to about 150

million ct/y by 2019, with output then falling back to 110 million

ct/y by 2030.

The one constant in the company’s estimates is Alrosa,

which, it predicts, will maintain current levels of production

right through the next decade and beyond. Rio Tinto and De

Beers will also maintain their respective production levels until

the late 2020s unless either can develop new capacity. The

slide will come more from the small players, which typically

have smaller, shorter-life resources.

In the end, for gem diamond sales it all comes down to consumers’

willingness and ability to spend money on jewelry. As

the report noted, “A continued source of both concern and opportunity

is the question of long-term demand for natural diamonds.

As a new generation of consumers — the millennials

— heads toward its prime spending years, the industry needs to

find ways to effectively engage with them.”

Conveyor structure at Lucara Diamond Corp.’s Karowe mine in Botswana, which

Conveyor structure at Lucara Diamond Corp.’s Karowe mine in Botswana, which

it

commissioned in 2012. The company is currently installing four more Tomra X-ray

Transmission diamond-recovery units, having already used the technology very

successfully to recover large stones.

Industrial Diamonds – The Overlooked Sector

For reasons that probably need no explanation, most peoples’

focus is invariably on gem-quality diamonds. After all, jewelers

shops sparkle on the high street; outlets for drill bits and abrasives

are usually lurking in some dark recess of an out-of-town

industrial park.

Yet there is a huge and increasing market for non-gem diamonds

as well, a market now so large that natural diamond can only supply

about 1% of world demand. The other 99% is synthetic.

In terms of mined output, gem-quality stones make up somewhere

between 20% and 30% of total annual production. The remaining

70%-80% is destined for industrial uses — and it is this

volume (around 100 million ct in 2016) that makes up the 1% of

industrial diamond that is not supplied by synthetic material.

According to the commodities research firm, Transparency Market

Research, synthetic diamond is often preferred to natural material

for industrial purposes such as grinding, cutting and polishing

diamond because its physical properties can be modified according

to end-use requirements. Developed in the 1950s, two routes

are available for producing synthetic diamonds: the HPHT (High

Pressure High Temperature) or CVD (Chemical Vapour Deposition)

processes. The HPHT system involves replicating the natural formation

process for diamonds by applying high pressure and temperature

to carbon or graphite, while the CVD process operates at low

temperatures and pressures.

Today, the main producers of natural industrial stones and bort

(fragmented material) are the DRC, Russia, Australia, Botswana

and South Africa, which supply around 80% of the world’s annual

output. By contrast, China alone accounts for around 90% of world

synthetic diamond production, with the USGS estimating its production

at some 4,000 million ct last year. To put this in perspective,

U.S. production was 125 million ct worth around $1/ct.

In the 2017 edition of its industrial diamond mineral commodity

survey, the USGS pointed out that “constant-dollar

prices of synthetic diamond products probably will continue to

decline as production technology becomes more cost effective;

the decline is even more likely if competition from low-cost producers

in China and Russia continues to increase.

Putting some figures on this outlook, Transparency Market

Research estimated that the global synthetic diamond market

was worth $15.7 billion in 2014, with the company predicting

lower costs and an increase in the number of industrial applications

for synthetic diamonds will build the market to a value of

$28.8 billion by 2023.

Big Stones Sparkle

A feature of the period since E&MJ’s last major review has been

the number of large rough diamonds that have been unearthed

— an achievement in which some smaller producers can claim

equal credit with the industry’s long-standing majors. And they

have not been slow in advertising their successes either, presumably

working on the premise that successful, well-publicized

sales of large stones will do their share price no harm at all.

For example, Gem Diamonds discovered a 314-ct stone

at its Letšeng mine in Lesotho in May 2015, and two months

later had a 357-ct diamond in its safe — later sold for $19.3 million.

Also in 2015, Lucara Diamond Corp. discovered the 342-ct

“Queen of Kalahari” at its Karowe mine in Botswana, with the

US$20.6 million stone subsequently being transformed into a

suite of six pieces of jewelry containing 23 flawless cut diamonds.

Not all sales of large diamonds are successful, though, as

was shown in May this year when the government of Sierra Leone

tried to garner interest for a 709-ct rough stone that had

been found two months earlier. The top bid of US$7.8 million

was rejected as insufficient, according to a Reuters report, although

the price offered would suggest that the diamond was

not of a quality to match its size.

Lucara was also disappointed when the 1,109-ct “Lesedi La

Rona,” the second-largest gem-quality rough diamond ever discovered,

failed to meet its expected price of at least US$70 million

in June last year, although the company gained some recompense

as its 813-ct “The Constellation” had sold for US$63

million a month before that.

Even Rio Tinto has been in on the act, with the 187.7-ct

“Diavik Foxfire” discovered during 2015. By all accounts the

stone should have been rejected and sent to waste, but its elongated

shape allowed it pass through the scalping screen. The

sale price was not disclosed.

And not to be outdone, Alrosa reported the recovery in July

of a 75-ct stone and one weighing almost 110 ct at its Mirny

operations in Russia. In 2016, the company found a 207-ct diamond

at its Zarnitsa mine, the largest recovered since open-pit

mining started there in 1999.

As featured in Womp 2017 Vol 09 - www.womp-int.com