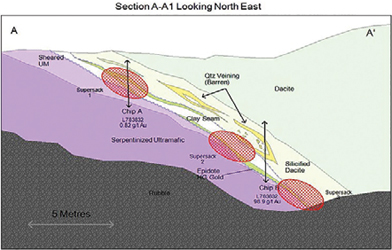

Sampling at Canadian Gold Miner’s West Matachewan project reveals an average feed grade

of 240 g/mt Au. Above, a sketch of the vein exposure. (Photo: Canadian Gold Miner)

Sourcing Finances After the Super Cycle

A credit crunch and a mining bear market have created a new generation of investors

— realists — making funding challenging for some.

By Jesse Morton, Technical Writer

The global downturn that started with a housing market crash a decade ago and continues in Europe was termed a “credit crunch.” While the central bankers move to exit the strategies deployed to ease lending and increase money velocity, in some sectors money remains tight. Manipulating interest rates and monetizing bad bets only goes so far. Miners, suppliers and their financiers say that, since the downturn, investors with expectations shaped by the crunch, new conservative investment vehicles, and high technology have changed the task of sourcing funds. A couple of recent success stories illustrate this point.

Targeting and Networking

In early February, Canadian Gold Miner

(CGM), a subsidiary of Transition Metals

Corp. with 165 square kilometers (km2)

of exploration projects on Ontario’s Abitibi

greenstone belt, announced sample

results from its West Matachewan project.

The project spanned 25 kilometers

(km) along the Cadillac-Larder break

west from Alamos Gold’s Young Davidson

mine. The 1.23-metric ton (mt) sample,

taken in July 2016, returned a feed grade

of 240 grams per mt (g/mt).

The project and others in the region are the company’s raison dêtre. Transition spun off CGM with the mission to “aggressively” secure “exploration-stage projects” around “key breaks and structures, like the Cadillac-Larder break and Ridout Structure,” said Greg Collins, CEO, CGM. The key word is aggressive, and CGM was to take chances on new projects Transition simply couldn’t.

“In the last downturn, when financing was difficult to secure, interest just wasn’t there,” he said. “We saw an opportunity in those dark days to try to consolidate and build the kind of projects that we felt confident would attract investment when the market turned around.”

West Matachewan was one such project. Investors surely would notice when a “10-kilogram sample of oversize screenings returned an assay of 2,269 g/mt,” he said. That sample and others were taken from three sites at 5 meters (m) apart in a zone that exhibited “appreciable but highly variable grades,” CGM reported.

The zone of veining, exposed by a mechanical excavator, ran 35 m, with an average true thickness of 1 m. “The zone consists of quartz-carbonate veining and silicification developed along a faulted contact between serpentinized ultramafic intrusive rocks and dacite, striking northwest and dipping approximately 55° northeast,” the company reported. The estimated head grade came in at 256.5 g/mt. The tailings averaged 98.3 g/mt.

Roughly three months later, CGM announced it closed a private placement totaling $817,250, with proceeds going in part to drilling at the project. The financing was arranged by Gravitas Securities. Details included the issuance of almost 5.3 million units of common share and warrants, issuance of 115,000 flow through eligible shares, stock options for employees, and an agreement to complete additional flow through financing. The placement was one step on a path to going public as early as this fall and raising between $10 million and $20 million over a half decade, Collins said.

Collins attributed the successful placement ultimately to the potential of the project. Next in importance, he said, comes “networking and putting a lot of effort into communicating with the right people, getting the story in front of the right eyes.”

Bankrolling a new project in the current market can be particularly challenging, Collins said. “It seems to be easier for those companies who have projects that are already at a much more advanced stage and have good liquidity to attract the lion’s share of investment,” he said. “What we have been successful doing is identifying and connecting with the right type of investor.”

The right type of investor is a different animal than previously, due to the credit crunch and subsequent mining bear. “That downturn really did decimate the networks that were in place,” Collins said. “The networks that were out there trying to solicit investment into mining stocks during the good times are totally different when you are not faced with those conditions.”

Gravitas represents “a new group that is coming into this space out of the downturn,” he said. “Gravitas was interested to partner in CGM for the same reason a lot of the seed investors were attracted to getting involved. They see it as an early stage opportunity for them to gain exposure to a new project.”

Collins said he remains optimistic that market conditions are improving for new mining juniors. “Certain things have changed in the market, particularly since the new year, that have been encouraging,” he said. “There are groups out there that are creative and a bit visionary. Ultimately, these are probably new groups.”

That advice is echoed by others in the sector.

Seize the Opportunity

In mid-February, specialty drilling company

Energold announced it had entered a binding

term sheet with Extract Advisors LLC

for a $20 million loan. Its stock price responded

accordingly. Two weeks later, the

company announced it had been named to

the Toronoto Stock Exchange Venture 50.

The loan would accomplish many things. Primarily, it would allow the company, with 150 drill rigs in a handful of sectors in 25 countries, to discharge a $10 million convertible loan from 2010. That original loan had financed the company’s pivot from mining into the Canadian oil sands and the energy sector in general. In 2014, it rolled over to $13.5 million. Payables accrued. Oil tanked. And then last year, amid signs the mining bear was bottoming, the option to convert arose. “That has always been an option that the convertible debt would be converted to shares when the market improves,” Jerry Huang, director, corporate development and investor relations, said. “Things were looking optimistic.”

The company could either discharge the debt or roll it over. “We had that cash. We could pay off the $13.5 million from 2014, but if we did that we would have very little buffer if things were to continue sideways,” Huang said. “We decided to be more conservative, and that is where the current round of $20 million came into play.”

Huang said the company courted a number of suiters, contacts both new and old. The company signed with Extract for a 60-month $20 million secured convertible loan. Extract, he said, was “brand new.” The conversation was born from prospecting, cold calling and then qualifying the natural resources investment manager, Huang said. “I found Extract through prospecting similar funds that have interests in unique service situations in the mining sector,” Huang said. Extract was interested in mining, but not in specific projects. “It was a good pitch, a well-positioned pitch to a generalist fund that wanted some exposure to mining but maybe not necessarily a mining project,” he said.

The conversation graduated to an offering for a “positing in this unique investment vehicle that wasn’t open to the public,” Huang said. “It culminated in the deal where they also asked for management and other funds to step in and show a vested interest.”

Extract would pay $15 million. The balance would be provided by a syndicate of lenders, to include existing debenture holders, new investors and company insiders. Among other terms, the loan could be converted into common shares for $0.85 per share. Energold would also issue more than 4 million warrants. And Extract gets to nominate a member to Energold’s board of directors.

With the announcement of the deal, Energold share prices doubled. “The delay and the due diligence to working out the deal in the last five months has really dropped the share price quite a bit because it gave an overhang on the stock,” Huang said.

The deal, he said, provides working capital and lightens liability. It could also enable the company to grow. “As the sector improves, we’re looking at countries that haven’t seen activity in years, like Peru.”

Huang said the deal in general helps the company breathe easier, especially in light of the difficulties in sourcing funds today. The mining bear and the credit crunch “really changed the way financing happens,” he said. “The fundamental structure of the financial sector, the boutique investment banks and the brokers sector, through additional requirements on compliance, KYC (know your clients), all changed with low fees, robo-advisors, and of course, the original ETFs, which had very low requirements for active investment management.”

Previously, a junior minor could go through a fund manager to get backing, Huang said. “It is harder and harder to see those because more and more clients and customers, at the end of the day, vote with their wallets, and they go with passive investments, which is computer indexing,” he said. “There is nobody to pitch to or no PM to convince to buy your share in prior placements.”

As traditional venture capital channels dried up, new money replaced it via royalties, streaming, debt financing and strategic offtakes, Huang said. “Offtakes, streaming and royalties really only apply to midstage development projects. There’s still not very much in between,” he said. “You need some venture capital money for that early greenfield project, which has no road, no access, and is in the middle of nowhere.”

Huang said companies seeking financing have to shop around and take advantage of the opportunities presented. “Like any sales process, it is a law of averages,” he said. “The more you reach out, you will reap more rewards.” He advised using a “wide net casting approach, where you are going through a large number of prospects and narrowing them down.” If possible, go through the specialized channels available: commodity brokers and trade commissioners, whether national or international, he said.

Networking through existing banking relationships could produce leads or referrals, Huang said. “In our case, it was a combination of everything: It was a prospect cold call, trust-building and relationship-building through banks that we all know,” he said. “You have to stay optimistic that the market will turn and hard work pays off.”

Optimism, networking, cold calling, relationship- building, and showcasing project strength are all crucial efforts within a successful financing campaign. And in some cases, in the current climate, success at those efforts may not be enough.

Get Creative

Simply put, money no longer flows where

it did prior to the crunch and mining bear.

Any miner or supplier should build this

reality into their procurement strategies,

investment bankers and institutional investors

say.

This development has created space for private equity and hedge funds. It has reinforced the need for retail investors, he said. “Companies have had to get creative with joint ventures, streams and royalties, too.”

Campbell advises companies to align with strong financial partners early. “You need loyalty among key shareholders to weather the storms,” he said. “You also need visibility.”

Young companies, he said, should be prepared to market themselves frequently. “Exploration is the toughest, highest risk segment of the mining market,” he said. “No one should be under any illusions that financing such companies is hard work.”

The project is the most important piece of any investment thesis,” Campbell said. However, he said, it is far from the sole piece. “Investors will look for the strength and track record of the management team and the board of directors,” he said.

Factors like trading liquidity and analyst coverage will also draw investors in, he said. “Some investors choose to zero in on the capital structure of the company such as insider ownership, previous financing prices, the existence of debt and the absolute share count.”

Non-mining qualities of the project also bear consideration, Campbell said. For example, “the project may have strong technical merit, but be in too risky of a political jurisdiction.”

Promote Strengths

Essel Group Middle East (EGME) reported

it considered first the project, and then

the technical record of Gensource Potash

Corp., before launching a joint venture

(JV). “We have always believed that quality

assets demand value,” Punkaj Gupta,

joint managing director, group CEO,

EGME, said. “Coupled with that, if you

can achieve operational efficiency, this

will ensure lower break-even.”

Per the terms of the agreement, valued at more than $200 million, the JV company, Vanguard Potash Corp., will finance, develop, engineer, construct and operate a mine and processing plant to produce potash from the Vanguard asset near Eyebrow and Tugaske in Saskatchewan. Vanguard will also market and sell the potash product.

Gupta advises companies prospecting for financing to focus on three things: demonstrate operational efficiency, promote high-quality assets, and ensure production efficiency. “These three factors are crucial to ensure that companies can face the rough weather of a downtrend and deliver profit expansion when the tide turns.”

Any consequence of that will fall on underperforming companies, he said. “In our experience, there is always more demand for quality producing assets than for non-producing quality assets,” Gupta said. “As a result, the monetization of non-producing assets has suffered more.”

This is to say that risk is out and conservatism is hip in the investment community. The EGME strategy reflects this. “We remain focused on creating a quality producing- asset, which will ensure that once the cycle turns around, the expansionary valuation will be a game changer,” Gupta said.

Ensure Your Reputation

In a bear cycle, the big fish fund only the

most appealing smaller ones. Call it survival

of the fittest or simple consolidation,

what it means is a company seeking to

source funds should be able to market

itself, should have done its homework,

should be prepared to explore a range

of options, and may ultimately have to

surrender more autonomy than desired,

said Robert Carbonaro, managing partner,

head of investment banking, Gravitas Securities

Inc. “To survive, some companies

have had to submit to very expensive and

encumbering royalty and metal streaming

arrangements with private equity firms,”

he said. “It’s disturbing to see junior miners

having to resort to often usurious deal

terms, which provide relief in the short

term but jeopardize sustainability and

growth in the long term.”

Cash-rich mining groups like Osisko Royalties (and Osisko Mining), Eric Sprott, Agnico Eagle and Goldcorp have taken minor but strategic positions in many prospective juniors. These investments are not usually sufficient to bring projects to commercial production, but, Carbonaro said, are key to attracting more capital and advancing projects. “The price of these investments to juniors is that they are essentially ‘owned’ and have sacrificed a portion of their exploration upside leverage,” he said. These deals attract a lot of attention and are a good alternative in a luke-warm financing environment and when juniors can no longer postpone spending on mineral assets of merit.”

Within the last four years, the Gravitas flow through mining fund has contributed to the financing of 15-20 companies. The idea, Carbonaro said, is to reward “due diligence fundamentals.” Gravitas, he said, likes to see drill-ready projects and “are reluctant to get involved with companies that haven’t done all they can in preparation for drilling so to give them the best chance of success.” By preparation, he means adequate exploration, sampling, mapping and modeling.

Carbonaro said juniors should focus on protecting their reputation through the peaks and troughs of the cycle. “Without a good reputation, both ethically and technically, your chances of survival and success in the exploration industry are slim and rightfully so.”

The current uptrend in mining may, unfortunately, amount to a bull run in a bear market, Carbonaro said. “I believe that generally the industry needs more time to work off stockpiles for most base metal and bulk commodity prices to appreciate to a level that brings greed back to the market,” he said. The long-term impact of the bear will be a shortage of qualified workers when it ends. “This past downturn has been very hard on new graduates in geology and mining engineering who were mesmerized by all of the super-cycle hype but ended up jobless on graduation and were forced to change disciplines,” Carbonaro said. “Therefore, Canada has lost a generation of professionals, which will certainly be a big problem when commodities are again in short supply as mines won’t have experienced professionals to build and operate the mines and the whole boom and bust cycle could be even more volatile than past cycles.”

*Editor’s Note:

The information provided by Campbell,

and the following sources, is neither a solicitation nor

an offer of securities.