South Africa’s Mining Industry Opposes New Mining Charter

In June, the Department of Mineral Resources (DMR) promulgated a new version of the Mining Charter that differed substantially from its previous version. The charter, since it was introduced in 2002, has provided rules for black participation within the mining sector. However, previous versions have always been drawn up by consensus between government offi cials and the industry. This time almost no consultation took place, the Chamber of Mines said, which represents around 90% of the industry. The chamber will seek an immediate interdict against the charter.

The version of the charter published brings out a variety of brightly fl ashing red lights, said Mxolisi Mgojo, president of the chamber. “We believe we have no choice but to apply for an interdict on the charter,” he added.

The issue of the charter has been simmering for some time. The DMR has been at odds over the revisions that the government has been pursuing. However, the latest document was published without consultation, to the outrage of mining companies who were caught by surprise.

“Today we see additional issues that have not seen the light of day before,” Mgojo said. At a hastily organized press briefing, chamber offi cials said they had only seen the fi nal charter “40 minutes ago.”

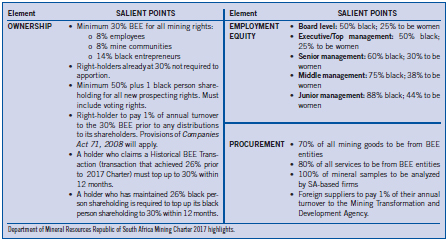

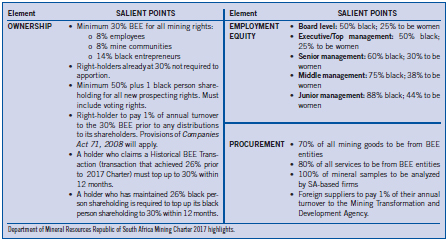

Among the key provisions are:

• Raising black ownership threshold to

30% from 26%;

• 50% plus one share black ownership

of prospecting rights, also up from 26%

to 70% of procurement of mining goods

to be purchased from black economic

empowerment companies;

• The demand for companies to pay 1%

of their annual turnover to the 30%

black economic empowerment (BEE)

structure before any distribution to all

shareholders; and

• Scraps the provision that previous black

empowerment arrangements be credited

even if the black shareholder has

since exited the company.

The chamber said it was too soon to discuss the specifi cs of the provisions, but its primary objection was that mining companies had almost no say in the new law. Roger Baxter, CEO of the chamber, noted that the last meeting held between the chamber and DMR was two months ago. However, Baxter said the provision of 1% turnover to black shareholders amounted to a tax on other shareholders. He also objected to the 70% local contractor requirement.

“This is going to be impossible to achieve because a lot of the big manufacturers are not going to set up shop in South Africa,” Baxter added.

He noted that previous versions of the charter had been negotiated between the mining sector and DMR. “It was entirely a DMR charter and it does not have the industry buy-in,” Baxter said. “Lots of those issues we have only seen today.”

Baxter said the new charter would only add to the uncertainty plaguing the local industry.

In talks with government over the issue, the DMR focused almost entirely on putting an end to retrenchments and showed little interest in other issues that could foster growth. For instance, it has become almost impossible to secure exploration permits, Baxter said.

“Greenfi elds mining is dead,” Baxter said. “Companies cannot get prospecting permits. Only brownfi elds exploration around existing mines.”

The promulgation of the new charter is likely to be the biggest crisis the industry has faced for some time, and shares of local operators plunged up to 5% after the news.

President Jacob Zuma is deeply unpopular following a series of corruption scandals involving him, his family and business associates. At the same time, the country has now tipped into a recession and been downgraded by ratings agencies to junk status, considerably raising the cost of capital.

Unemployment also hangs at around a third of the working age population — among the highest of any industrial economy. As a result, Zuma has been making populist noises around the nationalization of land and “radical economic transformation” to appease critics.

There is speculation that the charter may be another populist attempt to shore up his fl agging support. Mines Minister Mosebenzi Zwane alluded to as much in a prepared speech on the charter.

“The need for more radical measures in order to meet the socioeconomic needs of our people has never been greater than it is right now,” Zwane said. “As a country with a substantial amount of untapped mineral resources, we have a unique opportunity to use these minerals as a catalyst not only to adopt more aggressive economic growth efforts, but to catapult South Africa’s economy forward.”