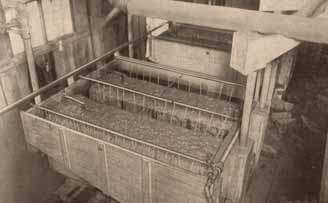

A steam shovel exposes development drifts at the Utah Copper Co. pit in Bingham Canyon

(September 7, 1907).

E&MJ Turns 50 at the Dawn of the

20th Century

The Great War pushes the prices for base metals higher as radical labor movements

hamstring operations

By Steve Fiscor, Editor-in-Chief

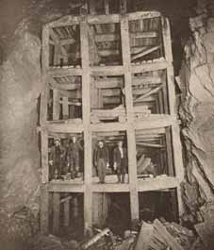

The automobile has replaced the horse-drawn carriage in urban centers. Trains and trolleys are consuming more steel and copper. A similar transition is occurring in the mines, where larger and larger electrically and diesel-powered equipment is starting to provide economies of scale. On the surface, steam shovels and draglines are moving ore and overburden, and mucking machines underground are loading ore cars pulled by locomotives rather than horses. The changes are also affecting the role of the miners in the pits. E&MJ routinely reports on labor disturbances created by the Wobblies or the International Workers of the World (IWW), whose radical, anarchical style will eventually be its undoing. A major labor movement is beginning to take shape worldwide.

The editors and readers still refer to E&MJ as a paper even though it is starting to look more like a magazine with black-andwhite photography. The title is still a weekly, but it has grown to 100 pages or more with advertisements. Internally, the leadership at the magazine changes as does the ownership.

While E&MJ provides news from around the world, it still focuses primarily on U.S. mining, and business is booming for the American mines in 1916. The U.S. now produces more coal than England. Copper prices are at an all-time high. And, there is plenty of investment capital for the mines and mills.

Editorial and Ownership Changes

At the turn of the 19th century, E&MJ was still published by

The Scientific Publishing Co. Richard P. Rothwell was the editor

and he served as co-editor with Rossiter W. Raymond from 1874

to 1889. He established E&MJ in its early reputation as a journal

of mining economics and technology. He was also an active

sponsor and founder of AIME, and was president in 1882. He

died in 1901.

In January 1902, a semimonthly publication, Mining and Metallurgy, was merged with E&MJ and David T. Day was appointed as editor. “Day is supported by Raymond, Frederick Hobart and Walter R. Ingalls, who are serving as contributors. His brief one-year association with E&MJ has a nominal infl uence and he retires. His career of 28 years with the U.S. Geological Survey earned for him the sobriquet of ‘father of the Mineral Research Division.”

In 1903, T.A. Rickard was appointed editor of E&MJ. Rickard was a famous mining engineer and mining writer. He wrote extensively about his travels, and those stories were published routinely in E&MJ, The Mining & Scientific Press in San Francisco, and the Mining Journal in London. He also wrote several books discussing mining, history and journalism, presented papers at AIME meetings and spoke at mining colleges. He had a rapport with Raymond and Rothwell and wrote kind words about Hobart and Ingalls in his memoir, Retrospect. Rickard gave financial and editorial control of E&MJ to a large group of mining engineers. He promoted lively discussion of technical topics, notably on ore deposits, mine sampling, and pyrite smelting.

Rickard and Johnston, however, did not see eye-to-eye. When Rickard accepted the position as editor, he arranged with Johnston for the issue of $200,000 ($5 million today) or 8% preferred stock, of which he took $50,000; the remaining $150,000 was purchased by fellow mining engineers. Johnston held $300,000 in common stock, which gave him control, but he could only sell his stake to someone who met the approval of the other shareholders. Rickard and the other shareholders forced Johnston out. He wanted to sell his stock to John A. Hill, but that proposal was vetoed and he sold his stock to H.M. Swetland, a publisher of automobile papers. After about nine months, Swetland sold his shares for a handsome profit to Hill.

E&MJ not only survived, but thrived during this turbulent period. In 1905, Walter Renton Ingalls was appointed editor of E&MJ and he remained at the post until 1919. He inherited from Rothwell the statistical and economic traditions of E&MJ and developed a method of metal market reporting that gained worldwide acceptance. During his tenure, the technical scope of E&MJ was broadened to such an extent that it eventually abandoned coal mining, which led to the creation of Coal Age to serve that branch of the industry.

U.S. Mining Highlights From 100 Years Ago

The U.S. mining industry experienced unparalleled prosperity in

1916. Due to high metal prices, E&MJ reported record outputs

in nearly every branch of the industry, both in tonnage and in

the value of the production. This was especially true of copper,

zinc, lead and iron; gold and silver did not experience a boom

per se, but owing to the great prosperity of the country, plenty

of investment capital was available for precious-metal mining.

A restriction on imports led to the development of many new

mineral properties in this country.

Labor participated in the prosperity in the form of bonuses, straight wage advances and increases based on the price of the metals. “Labor was hard to get, as a result of the extraordinary activity, and was also inefficient,” E&MJ reported. Considering conditions, serious labor disturbances were not numerous and were confined to the ending of the Clifton -Morenci strike in January; the IWW disturbance on the Mesabi Range, where a number of the underground mines were closed, though total iron-ore shipments were not curtailed; and the closing of most of the Mother Lode mines in Amador County, California, for seven weeks, the miners returning to work on the old basis at the end of that period.

Being primarily a copper-producing state, Arizona prospered enormously in 1916. Plant extensions were made at nearly all the established properties and at the El Paso Smelting Works, which treated a considerable amount of Arizona ore and concentrates. E&MJ noted the important plans of the Inspiration Consolidated Copper Co., the practical completion of the New Cornelia Copper Co.’s 5,000-ton leaching plant, the grading for Ray Hercules’ new mill and the extraordinary boom in the Jerome district. The Tucson, Gila Bend & Ajo Railrod was completed and stimulated further development in the Ajo district. The International Gas and Electric Co. of Nogales extended its electric-power line to the Santa Cruz County mines.

In Colorado, the lead and zinc mines of Lake and Summit counties were extremely active, as was also the San Juan country in the southwest. New discoveries of ore at depth in the Cripple Creek mines kept that famous gold district active without the added incentive of increased price for its products.

In Michigan, the copper companies of the Lake Superior district achieved record production in 1916. “Nearly every company increased its output and some companies that had not produced profi tably for years were able to operate with a balance on the right side of the ledger,” E&MJ reported. Free from IWW disturbances that took place on the Mesabi Range in Minnesota, Michigan, took part in a rally in iron ore production. Cleveland-Cliffs Iron Co. at Ishpeming practically completed its preparations for placing the Holmes mine in the shipping list; the mine has the highest headframe of any Michigan iron mine.

The IWW strike in the summer of 2016 closed many of the Mesabi underground mines, but shipments were more than maintained out of stockpiles. Common labor at the end of 1916 was being paid $3/day ($75/day today) at nearly all mines. Electrification of mining equipment was marked in 1916, and there was a tendency toward heavier machinery. At the Mace openpit mine, Butler Bros. began using a 375-ton Bucyrus revolving shovel with an 87-ft boom. A dragline was used for stripping at the Warren mine by the Winston Dear Co.

Copper and zinc production in Butte, Montana, reached a surpassing fi gure, E&MJ reported, and many old mines in outside districts were reopened as a result of the high metal prices. Anaconda started its 100-million-lb electrolytic zinc refi nery and completed its construction campaign at Great Falls. The Black Hills district in 1916 produced about $7.5 million in gold, of which Homestake furnished approximately $6 million. The other production was mainly from the Golden Reward, Trojan, Mogul and Wasp No. 2. At the time, gold was valued at $20.67/oz.

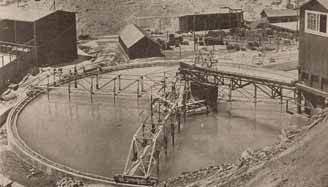

Being chiefl y a producer of base metals, Utah prospered enormously in 1916. All properties were operated under high-pressure conditions, the output of the mines at times exceeding the smelting capacity. Utah Copper Co., which produced about 85 million lb of copper in the first six months, was at the end of the year turning out more than 20 million lb/month and planning even more increases. More than 40,000 tons per day were frequently mined by the company in 1916.

In 1916, Alaskan mines generated more than $50 million in revenue, compared to $33 million in 1915. It was the copper mines that so greatly swelled the figures. As many as 18 copper mines were operating in Alaska, compared with 13 in 1915. Seven were in the Ketchikan district, eight in the Prince William Sound district, and three in the Chitina district. The great output from the Kennecott mines in the Chitina district overshadowed all other operations. Roughly 640 placer gold mines employed 4,600 men. The Alaskan camps of the Yukon basin are believed to have produced $7.1 million worth of gold in 1916.

The Use of Flotation and Leaching Evolves

The unprecedented market for copper during 2016 gave a tremendous

stimulus not only to the production of the metal and

consequent expansion of the reduction plants, but also to the

further development of the metallurgy of lean ores. In meeting

the great demand, many properties have been resurrected,

which, while dubious at $0.15/lb, are bonanzas at $0.25/lb

($5/lb today).

Advances in copper metallurgy at the time were taking place in three areas: flotation, leaching and the manufacture of sulphuric acid.

On December 11, 1916, the U.S. Supreme Court announced a decision in the suit of Minerals Separation Ltd. vs. Hyde, involving the basic patent for the flotation process of concentrating ores. The invention was held to be new and patentable in so far as the practice at the Butte & Superior mill is concerned, and the operations of the defendant Hyde at the Butte & Superior mill in Montana were held to be an infringement. A decision of the British House of Lords was referred to as having recognized the novelty of the invention. “But that the basic patent owned by Minerals Separation Ltd., upon which the froth-flotation process rests, is valid there is no longer any doubt,” E&MJ reported.

However, the gray area that separates flotation and leaching was a hotly discussed topic. “On mixed sulphides and oxides the feeling is not that the latter can be better handled by a separate hydrometallurgical treatment. When acids and soluble sulphides are added as flotative reagents with the object of coating oxidized material, flotation is really sailing more or less under false colors, as most of the additional recovery seems to be due to the dissolving of the copper in the acid and subsequent precipitation as sulphide, which is straight leaching; and as these reagents tend to react rather unfavorably on the legitimate recovery of the sulphide minerals present, it appears that the leaching operation should be conducted separately.”

Flotation processes were also being applied to both gold and silver metallurgy. “Although this was not considered possible a short time ago, a few recent installations have shown that highly successful results have followed the adoption of the process into this, for it, new field,” E&MJ reported. “The Goldfield Consolidated mill installed a large number of Callow cells designed to replace eventually the cyanide treatment. At this mill it is considered that flotation equipment treating a thousand tons daily may save up to $400,000 annually, without taking into account the higher extraction that may be secured.”

In another instance, Ralph W. Smith described at length in E&MJ (July 1, 1916) the treatment of an ore containing gold in addition to lead, silver and zinc, using the fl otation process and extracting the gold by it successfully. “One of the first things noted in the operation of the flotation machine was the fact that the free gold floated,” Smith said. “Assays showed that much cleaner gold tailings were being made than by any other machine in the mill. The percentage saving of gold reached about 85%.” While many cyanide plants continue to operate, E&MJ reported that some of them have been partly, and a few wholly, changed over into flotation plants.

While most of the mills making use of flotation have been those in which base metals are treated, in a number of cases precious metals have been recovered as a sort of byproduct, such as the silver recovered in the concentrates of the mills in the Coeur d’Alene district of Idaho, and the gold in the copper recovered in some of the Montana mines. It seems, however, that now flotation is likely to be used on purely precious-metal ores.