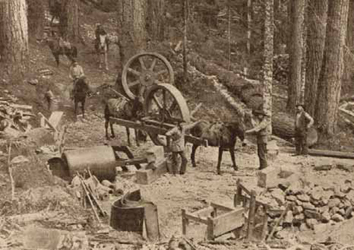

Miners transport a stamp mill 8.5 miles over a rough mountain trail to the Champion

mine in Lane County, Oregon, at an elevation of 5,200 ft. Two mules are used to pack

a 7-ft-diameter cam shaft pulley that weighs 800 lb.

E&MJ Satisfi es a Thirst for Knowledge

As the world’s appetite for minerals grows, the American mining sector gains steam

at the turn of the 19th century

By Steve Fiscor, Editor-in-Chief

Rossiter W. Raymond had passed the torch to Richard P. Rothwell. He became the editor, but had been working for E&MJ for nearly 20 years. The Scientifi c Publishing Co. published the title and the offi ces moved from Park Row to Broadway, and mining engineers visiting New York City were still encouraged to visit the offi ce. Raymond was now practicing law, but he still wrote regularly. More often, he revealed a melancholy fl avor as he wrote obituaries for friends that contributed to his success and vice versa.

The previous year (1895) was one of the most prosperous in the history of mining. The deals were getting bigger and so too were the scandals. E&MJ continued to expose fraudsters, but the scale was growing more and more immense as English investors began to buy western U.S. mining assets.

In the U.S., society was recovering from another fi nancial depression. Copper and coal production, the feedstock for industrial demand, was growing at an accelerated pace. Meanwhile, the world was moving away from silver to gold as a form of currency. Looking forward, 1896 promised to reset all records for U.S. mineral production.

Technology continued to advance. Many mines in the western U.S. were harnessing hydroelectricity. The mule was gradually being replaced by the machine.

The Mining Business in 1896

E&MJ estimated the value of the metals

produced from domestic ores in 1895

amounted to $241 million, as compared

with $194 million in 1894—an increase

of 24.2%. U.S. silver production was

starting to wane. In 1895, it dropped

to 41 million oz from 50 million oz in

1894. Even though prices increased from

$0.63/oz in 1894 to $0.65/oz in 1895 (a

dollar in 1895 would be worth $28.50 today),

E&MJ frequently reminded readers

that the production of silver would continue

to decline.

Coal production in the U.S. in 1895 totaled 195 million short tons compared with 170 million tons in 1894. The U.S. was rapidly moving up toward fi rst place as the greatest coal producer in the world.

U.S. copper production increased substantially in 1895 as domestic and European demand more than kept pace with increased supply. American copper production grew to 172,300 long tons (or 354 million lb) a 30-million-lb increase over 1894. “…as we pointed out in our last issue the copper in sight is less than at any time since 1887. A striking feature, and of interest from the home point of view, is that in spite of the increase of production and a good demand at fair prices existing abroad, exports have fallen in 1895 to 62,474 long tons as against 76,297 in 1894.”

Foreign copper production fell from 89,031 long tons in 1894 to 86,800 in 1895. “The improvement in copper is a real Godsend to Chilean miners of Antofagasta where costs are so excessive. Miners are now at work, where instead of fi ghting water as is so often the case, the water for the entire service has to be hauled 40 miles. This looks like an increasing problem for Chile, once the greatest copper producer in the world.”

The New York Coper Market

“The great fi nancial depression which

visited our country during 1893 cast its

shadows far into 1895. As during previous severe depressions, history repeated

itself in this instance too, and it took a

considerably longer time than could have

been foreseen, even by the shrewdest

business men, before the vitality of the

country was restored to its fullest extent.”

Manufacturing communities were among the hardest hit: “…a great many of the large railroad systems found themselves after the panic… as for a long time only the most necessary repairs were made, while there was practically a suspension of new orders for a period of about 13 months.” Construction activities were also greatly affected, especially in the rural areas, for manufacturing and private purposes.

Copper consumption suffered too. It was not until the spring [of 1895] that consumption became considerably larger and quickly absorbed the stocks, which had never been very large during the past two years. Demand was for electric purposes and wire-drawers found themselves busier with more orders on their books than at any period in the history of copper.

Enormous quantities of copper have been used for trolley wires, the extension of trolley roads in the suburbs of larger towns and connecting neighboring centers, and the conversion of horde railroads into electric lines having all at once made extraordinary progress…

“A most interesting statement is found in the annual report of the President of the Western Union Telegraph Co. for the year ending June 30, 1895, in which it is stated that during the previous 12 months 15,748 miles of new wire were constructed, of which over 10,000 miles are of copper, ‘in accordance with our policy of replacing the defective iron wires on our trunk routes with copper wires.’

The demand for copper did not escape the attention of the capitalists. In 1895, a large interest in the Anaconda Co. was transferred to foreign holders, who took one-quarter of the capital stock for $30 million at a price of $30/share, the par value being $25/share. “The Anaconda had always been a closely-held property, and the publication of reports by the company itself and by the purchasers’ experts presented the fi rst opportunity ever given to thoroughly realize the magnitude of this, the largest copper property in the world.” The only mines to compete with it in resources and in present output of copper are the Rio Tinto in Spain, which comes in second, and the Calumet & Hecla, Lake Superior, which is third.

In June 1896, E&MJ would report that the sale of the Hearst interest of 270,000 shares in the Anaconda mine for $27/share, to the London syndicate, represented by the Exploration Co., places “nearly, if not quite, one-half of that stock and perhaps the effective control of that company in foreign hands, practically those of the Rothschilds, who already control Rio Tinto and some other Spanish mines, and who, with the Anaconda output, will control 40% of the world’s copper.”

Gold Begins to Replace Silver

World gold production has, “for a few

years past, been the most engrossing

subject of discussion in the mineral industry.

The partial disuse of silver as

money throughout the world has greatly

increased the demand for gold and the...

purchasing power of gold has been an

all-absorbing topic of discussion.”

In the U.S., gold production has increased in all of the mining districts. The greatest has been in Colorado, “…the gold discoveries in Leadville, and the very active exploitation of the mines of Cripple Creek, the latest district, have raised production from $9.5 million, to $15 million. Nearly one-half of this amount, or $7.2 million is from the Cripple Creek district alone. Leadville produced $1.3 million. California has reached a total of about $15.5 million, owing to the working of many new mines and the reopening of old ones.

Cripple Creek’s production has reached levels which not even its most enthusiastic admirers ever dreamed; a record that has had no equal since the days of Leadville in the West.” Cripple Creek’s population has nearly doubled and the number of producing mines has increased nearly 100-fold.

E&MJ would later report that, on April 29, the town of Cripple Creek has been virtually wiped out by a series of fi res, “… which was more than suspected to be the work of incendiaries with the object of plunder, chiefl y directed against funds in the First National Bank.”

The destruction of the town by fi re does not affect the productive capacity of the mines, “but at the same time it cannot fail to produce a certain disorganization which will probably show itself diminished product this month. We have not the slightest doubt that the characteristic energy of Westerners in general, and Coloradoans in particular will cause Cripple Creek to rise like a Phoenix from its ashes...”

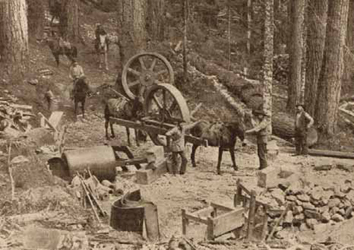

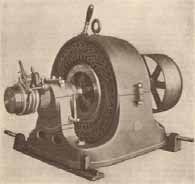

Electric Power Transmission

The development energy converted from

water power (hydroelectricity) for mining

purposes is steadily gaining favor. Perhaps

the most noticeable units in the

U.S. are two three-phase mining plants

(the Polyphase Tesla Motor), located near

Silverton, Colorado, and at Park City,

Utah. “The Silverton plant is the fi rst

three-phase plant installed in the Rocky

Mountain region. It uses water power taken

from the Animas River through a 3- x

4-ft fl ume, 9,750 ft long. The electrical

installation consists of two 150-kW generators,

driven by two double-nozzle Pelton

wheels. The current, at 2,500 volts, is

transmitted back up the mountains, a distance

of over three miles, to an altitude

of 12,300 ft. above sea level, where it is

used to operate various mining machinery

in the Silver Lake group of mines and

to drive the stamps and crushers in the

mill. Previous to the installation of this

electrical plant the mines were operated

by steam, and the coal cost is $8.75/ton

at the mine. These mines will likely save

$36,000/yr through the use of electricity.

“The Ontario mine located near Park City, in Utah, uses the power derived from the water of the drain tunnel of the mine—the most expensive tunnel ever constructed by any mining company.” Measuring three miles long, it discharges 1,000 cfm of water from its mouth. This water, under a head of 120 ft drives generators of the General Electric monocyclic type, which furnish current at 2,500 volts for transmission around the mountain to the Ontario and Daly mines, fi ve and a half miles distant, where it drives the mills and lights the surrounding buildings. Current from these machines is also taken to light the neighboring town of Park City.

“The San Miguel Gold Mining Co. are so well satisfi ed with the result of operating in Southeast Colorado, near Telluride, by long distance transmission, that they decided to largely increase their plant for themselves and neighbors, and the new plant is now being installed. This addition to the plant is supplied by the Westinghouse Co.

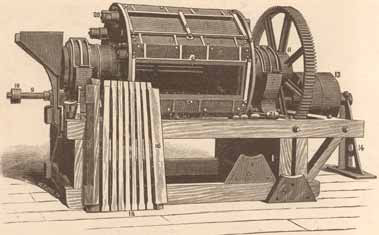

The Dodge Pulverizing Mill

“This mill, for pulverizing ore either for

amalgamation or concentration, has now

gone through suffi cient test during the

past four years in California, Arizona

and elsewhere...” The Dodge pulverizing

mill consists of a hexagon drum or barrel,

as shown, into which the ore, after

passing through the rock breaker, is fed

through a hopper. The barrel is lined

with forged steel bars (each of the bars

seen to the left of the side view form one

side of the hexagon), which are held in

place by wedges, secured by bolts and

steel springs. These bars are spaced at

½-inch and from a grating through which

the ore passes to the screens, which are

on each side of the hexagon and afford

a ready means of discharge for any ore

that is crushed fi ne enough to pass. With

the mill being hexagonal in shape, the ore

does not slide in mass, as is the case in

cylindrical mills.