Buenaventura CEO Roque Benavides warned participants at the Peru Gold Symposium about rising mining costs

Peru Keeps Gold Production, but Loses Weight Overall

The country’s mining industry has reached a transition point and its success could continue for a long time, depending on how it deals with the issues it faces today

By Alfonso Tejerina

The CEO of Hochschild Mining Ignacio Bustamante, president of the symposium, inaugurated the sessions on May 14 by outlining three challenges for mining in Peru: first, the need for collaboration between the private sector, the government and the society; second, the importance of creating value for all stakeholders; and third, the promotion of more value-added activities to no longer be a country that only lives off of its primary industries. The creation of a mining cluster is a potential solution to this final goal.

Probably the most powerful speech on the opening day was made by Roque Benavides, CEO, Buenaventura, which owns 43.65% of Yanacocha. Benavides warned about the gold industry’s rising costs: the industry average increased from $560/oz in 2010 to $643/oz in 2011. In the case of Peru, the rise of the Peruvian Nuevo Sol against the U.S. dollar also had an impact, as well as the new taxing regime by the Humala administration.

Benavides emphasized that in Spanish the word for tax is impuesto (imposed) and argued that the new system, which will pro-vide the government with an additional $1.1 billion annually, was an imposition that the mining industry could only comply with. He also lamented that mining in Peru, although it represents 15% of the GDP, accounts for 40% of the state’s rev-enue through taxes, which indicates the level of informality in many other indus-tries. He gave the example of the coffee business, which employs 200,000 people but only 10% of whom are formal, accord-ing to some estimates.

Benavides made a link between rising costs and decreasing competitiveness. “The Fraser Institute places us as the sixth country in the American continent; like in soccer, we are nearly the last ones. Chile, Mexico, Canada and Brazil are more com-petitive than us,” he said. He underlined the importance of falling gold, silver, cop-per and zinc output. “For the last three years, Peru’s production has decreased and that needs to make us think. We are pas-sively leaving the space for other countries. Obviously in dollars our revenue has increased, but that is given by the price. What matters is production,” he said.

One Pierina Per Year

When discussing gold production in Peru,

there are two ways to analyze the situation:

looking backward and looking forward.

Miguel Cardozo, president and CEO of

Alturas Minerals and one of the country’s

most respected geologists, provided in-sights from both perspectives. He noted

that Peru only produced 700,000 oz in

1992; then the industry boomed and the

country became Latin America’s leading

gold producer in 1996 (it still is today).

Output reached a peak of 6.7 million oz in

2007, before decreasing to 2011’s 5.3

million oz. As of today, Peru keeps its place

as the world’s sixth largest producer, and

Cardozo expects the country to maintain

output levels in the range of 5.3-5.8 mil-lion oz per year until the end of the decade.

However, the country cannot rest on its

laurels. Cardozo explained that Brazil has

revived its gold production in the last years,

while Chile, Colombia, Mexico and

Argentina are emerging gold producers. He

added a meaningful statistic: in 2007,

Peru represented 6.8% of the world’s gold

production and 56% of Latin America’s

output. In 2011, it was just 5.6% and

38%, respectively.

“Our dependence on high-sulphidation epithermal deposits is one of our greatest risks. We rely on large mines, but with a relatively short lifespan. Moreover, current production figures include many small mines that also will be exhausted very soon. They are contributing today, but will not be there tomorrow.” Cardozo noted that the contribution of large copper porphyriesa to the country’s gold production will increase over the next years, with projects like Las Bambas (Xstrata) and Galeno (Minmetals/Jiangxi), around 2015; and Conga, if finally approved, around 2017.

Cardozo outlined the latest gold pro-jects to come on stream in Peru: Anabi and Buenaventura’s La Zanja in 2010; and Tantahuatay (co-owned by Southern Copper and Buenaventura), Buenaventura’s Breapampa and Xstrata’s Antapaccay copper-gold project in 2011-12.

“We currently produce around 5.3 mil-lion oz/y, and that’s the amount of gold that we should discover and develop annually to keep our production levels in the long run. It is a big challenge: it is like having to dis-cover one Pierina every year. It won’t be easy,” said Cardozo.

The Competitiveness Issue

To achieve this level of discoveries, a lot of

money needs to be put in the ground.

However, as is happening in gold produc-tion, Peru seems to be losing weight in

exploration when compared to other juris-dictions. In 2009, Peru was home to 7% of

the world’s exploration budget for nonfer-rous metals, according to the Metals

Economics Group Report. In 2010, it was

5%. In 2011, it had dropped to 4%, less

than Mexico (6%) and Chile (5%). In

absolute terms, exploration expenditures

have increased significantly. Yet, it is the

emergence of new jurisdictions that worries

some Peruvian leaders.

Fernando Sánchez Albavera, the first Minister of Energy and Mines under the Fujimori administration in the 1990s, gave a speech on the importance of mining for Peru’s sustainable development that con-tained some pessimistic views, among which: the world’s mining market is $400 billion, therefore Peru does not even repre-sent 10% of it; Peru is a mining country, but a mining country with small income; Peru only has one mining project among the world’s 10 largest gold mining projects, and that project (Conga) is under fire; final-ly, Peru’s mining production is far from matching the country’s potential.

Competitiveness in the Americas was the theme of another presentation by Noé Vilcas, general manager, Minera Oro Vega, a subsidiary of International Minerals. Vilcas’ first slide was about “the tax myth,” and showed that corporate taxes in Latin America are not lower than those in North America, with the exception of Chile. Colombia, Brazil, Mexico and Peru have tax burdens of between 40% and 50%, while in Argentina, Bolivia and Ecuador they go beyond the 50% barrier.

In the particular case of Peru, Vilcas said: “We have reached the investment grade, we have a solid economy, we have not been affected by the different econom-ic crises, and all this has made us evolve, we are not as promotional as we were 15-20 years ago.” This also happens in other jurisdictions in the region.

So, Vilcas said, if 15 years ago Latin America offered lower capex and opex costs, lower taxes, shorter permitting costs, and a low risk of government interference, today costs are higher due to the U.S. dol-lar devaluation, there are higher taxes, per-mitting times are dramatically increasing, and countries are keener to interfere in the ownership of natural resources.

Peru has seen excellent developments in gold mining, including very low-cost operations such as Barrick’s Lagunas Norte. However, what projections can be made for the future?

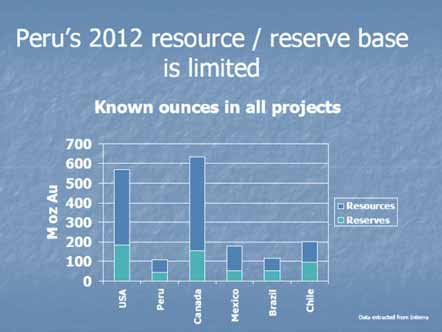

With data extracted from Intierra (including companies from the public spec-trum only), Vilcas demonstrated Peru’s very limited gold resource and reserve base (See chart above): lower than in Mexico, Chile and Brazil, and much lower than in the U.S. and Canada. Vilcas also noted that Peru has aging mines and a weak pipeline of new gold projects. Vilcas also pointed out the alarming fact that Peru already receives less gold exploration expenditures than Colombia. He anticipated that if the situa-tion is not reversed, production (“and hence taxes”) will drop steadily in the next decade.

Finally, with regard to the general com-petitiveness of Latin America, Vilcas noted that while Chile is the most attractive country in the region, some of the best investment incentives are already in place in North America. He specifically men-tioned Nevada’s fast-track procedure to develop projects, Canada’s flow-through system and Québec’s tax rebates. He also emphasized that Canadians have been smart to create a mining-related capital markets system that probably represents a tax revenue greater than mining itself.

McEwen: We’ll See $5,000 Gold

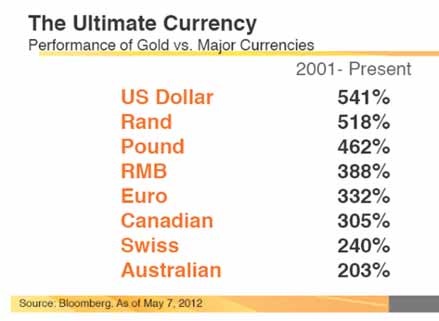

The matter of where gold prices are headed

was also at the core of the discussions at

the symposium. Although he does not have

assets in Peru, Rob McEwen, chairman and

CEO, McEwen Mining, was invited to give

his views on the global gold market.

Describing gold as “the ultimate currency,”

McEwen compared the performance of

gold against the world’s main currencies

since 2001. Results show that gold has

outperformed the U.S. dollar by 541%, the

euro by 332% and the Australian dollar by

203% (See chart at bottom of p. 93).

McEwen showed the extremely close correlation between the U.S. level of debt and the price of gold since the beginning of the century. He suggested that with $15.7 trillion of deficit and a gold price of $1,600/oz today, we could see gold at $2,600/oz in 10 years, when the U.S. deficit is expected to reach $26 trillion. “This is just the start. We are going to see a much higher price of gold. I’m looking at a price of $5,000/oz,” he said.

With that in mind, how can people invest in “the ultimate currency”? McEwen went through the three options: the cum-bersome process of buying physical gold, the ease of investing in gold exchange trad-ed funds (ETFs), or the confusion of decid-ing which gold stock to buy.

He noted that the ETF market is valued today at $122 billion, which is equal to the market capitalization of the four largest gold producers worldwide.

McEwen said that gold stocks have not followed the increase in the price of gold in the last years, which he attributes to the fact that CEOs have very limited ownership in the companies they run (“close to zero”) and that with 2,800 public exploration/ development/mining companies world-wide, investor confusion is widespread.

Aram Shishmanian, CEO, World Gold Council, further illustrated the importance of the ETFs market. “ETFs have re-ignited the role of gold in the financial system. Gold is now a financial asset,” he said.

According to his statistics, gold de-mand reached a peak in 2011, in both ton-nage and value ($200 billion). Some fac-tors that explain this figure are the actions of central banks, which reversed their decade-long tendency of being sellers in the market to become important buyers, and the “breathtaking” growth in demand from the East (China and India alone rep-resent 55% of the global demand).

As the leader of an organization that aims at the long-term sustainability of the gold business, Shishmanian warned that the mining industry will have to adapt to a whole new scenario.

“40% of gold supply is recycled. 10 years ago it was about 15% or even less. I can easily see a situation where recycled gold exceeds new production. This is going to change the mining industry. The ques-tion is, how do we navigate this uncertain-ty?” he asked.

Silver

As part of the Second Silver Forum, a num-ber of speakers, including Jaime Lomelín

of Fresnillo, Jorge Ugarte of Pan American

Silver, Eduardo Hochschild of Hochschild

Mining and Juan José Herrera of Volcan,

discussed the latest trends in the silver

market and gave an update about their

respective companies’ production data.

Here is a summary of silver’s facts and figures: the silver market was valued at $32.1 billion in 2011, which means it is the fifth largest non-ferrous metal in terms of market value (it was seventh one year before). The total silver offer in the market decreased to 1.04 billion oz in 2011, even though silver production from mines in-creased for the ninth year in a row, reaching a record 761.2 million oz. Of this, only 29% came from primary silver operations, while the rest (71%) was extracted as a byproduct of other minerals such as copper and gold.

In 2011, Poland’s KGHM Polska Miedz became the world’s largest producer (ahead of BHP Billiton and Fresnillo) with more than 40 million oz. Country-wise, Mexico strengthened its leadership, as it increased production by 8% last year (totaling 153 million oz) while Peru’s decreased by 6% and went under 110 million oz. China, 11% up with 104 million oz, already threatens Peru’s second spot in the ranking.

Total silver demand contracted in 2011 but going forward, the use of silver in industrial applications is expected to con-tinue compensating the unstoppable decrease of the photography industry as a source of consumption. The arrival of silver ETFs a few years ago and the significant increase in the demand for coins and medals reflect the growing appetite of investors for safe haven assets.

Moving forward, the price of silver should be less volatile and more pre-dictable, said Herrera of Volcan.

Finally, as in gold, production costs increased in the silver business from an average $5.47/oz in 2010 to $7.25/oz in 2011. Herrera outlined four reasons for this: pricier labor costs, lower grades processed, higher energy prices and a weak U.S. dollar.

Informal Mining

The organizers of the symposium reserved

a session on the third day to discuss Peru’s

illegal mining problem, which has serious

economic, environmental, social and pub-lic health implications. In the particular

case of gold, it is estimated that 14% of

Peru’s total gold production (around

737,000 oz) comes from the region of

Madre de Dios, where gold is exploited ille-gally causing tremendous environmental

damage. Interestingly enough, while over-all Peruvian production has been decreas-ing, in this region it grew by 35% last year.

Antonio Brack, father of the Ministry of the Environment created in 2008, gave a presentation on Peru’s two parallel mining realities: formal mining, with more than 800 mines respecting the regulations (including environmental impact assess-ments and mine closure plans) and the uncontrolled illegal activity. Brack pointed out that the mercury dumped into the rivers of Madre de Dios pollutes 250 km of water, reaching the Brazilian town of Porto Velho.

Peru’s Minister of Energy and Mines Jorge Merino, who later closed the sympo-sium, assured that there would be “no steps backward” in the fight against illegal min-ing, although he differentiated between “illegal” miners and “informal” miners, the latter of which can enter a two-year process to join the ranks of the formal mining indus-try. Merino assured that this gradual process does not mean that the illegal miners are getting their way; however, critics accuse the government of being lenient with them on the grounds of promoting “social inclusion,” one of the Humala administration’s mottos.

Merino highlighted the country’s $53 billion mining projects portfolio and the high level of respect for the legal frame-work and contracts signed, unlike in other countries. He also announced the creation of an Institute of Mining Planning that, together with the private sector, should ensure the tidy and competitive develop-ment of the sector toward the future.

Conclusion

Peru’s mining industry seems to be in a time

of transition. In gold, its best moments pro-duction-wise have already been left behind.

Copper offers great growth prospects, but the

general competitiveness of the sector has

decreased as other countries have joined the

game. With higher taxes, higher costs and a

stronger local currency than in the 1990s;

and with the persistence of a number of

social conflicts (the one against Xstrata at

Tintaya being the latest case in point), the

industry will have to work hard to assure the

long-term sustainability of the industry.

There is a lot at stake: the sector cur-rently provides 177,000 direct jobs and half a million indirect jobs, according to figures given by Roque Benavides. A further 1.9 million Peruvians rely on the wages earned by these workers. As the country’s Finance Minister Miguel Castilla pointed out, the fact that mining represents such an impor-tant chunk of the country’s revenue is an important weakness, due to the nearly per-fect correlation between the state revenue and the volatile international mineral prices.

Considering only 1% of the Peruvian territory is under exploration or exploitation activity, Peru should be able to continue its success of the last 20 years and carry the economic benefits of the industry into the next decades.

Alfonso Tejerina covers Latin America for Global Business Reports. He attended the Peruvian Gold Symposium on behalf of Engineering & Mining Journal. He can be reached at: alfonso@gbreports.com