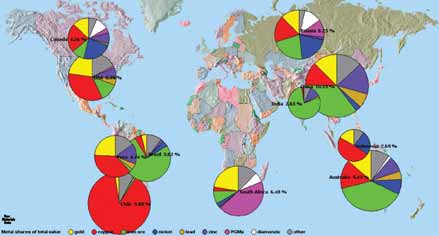

(% of total value of all non-fuel minerals)

Source: Raw Materials Data, Stockholm 2008.

Global Mining: New Actors, New Script?

Against the backdrop of increased societal demands being placed on mining, the

author discusses some of the challenges faced by the industry, based on his keynote

presentation at the PDAC 2008 Convention in Toronto

By Magnus Ericsson

At the same time, society’s expectations of the exploration and mining industry are growing rapidly and the industry is receiving increased political attention. Barely has the industry started to come to grips with its image and environmental footprint when new issues arise. Metal and mineral supply is becoming a concern in the industrialized countries, and developing countries want a larger share of profits.

Despite cost increases for many inputs, and operating cost increases at most mines, the profitability of mineral producers has exploded. Fortune Global 500 companies in the extractive industries (including oil) reached an exceptionally high profitability in both 2005 and 2006, compared with large companies in other sectors as well as historically. The average profit measured in percent of revenues was between 25%–30% in 2006 compared with less than 20% for the pharmaceutical industry, for example; and 5% as recently as 2002.

The global mining industry faces one main challenge: To deliver sufficient volumes of metals and minerals at prices which do not fuel inflation or encourage substitution, while plowing back a reasonable share of profits into local and national host economies.

When trying to meet this challenge a

few points must be kept in mind:

• Exploration and mining remain cyclical

businesses. Mine output will increase

and gradually catch up with demand, but

in the next few years it seems likely that

metal use will continue to grow at a higher

pace than it did during the end of the

20th century and hence the cyclical

swings will be on an upward trending

curve. Metal use is solidly underpinned

by both personal demand, as standards

of living improve, and by infrastructure

investments in countries other than

China and India. The present boom has

already lasted longer than any others

since World War II and the “super cycle”

is a fact. There is no imminent threat to

the boom by the incipient recession in

the United States, but the risk of indirect

effects due to decreased demand for

Chinese and other emerging-country exports

is real.

• There is a need for a new type of international

cooperation to facilitate the use

of minerals as a lever for economic and

social development in developing countries.

This is necessary to ensure that mistakes

of the past are not repeated, when

an insufficient share of profits flowed

back to host countries and local communities.

Many countries experience largescale

mining investments for the first

time and their governments have no history

on which to build policies. Cooperation

between developing countries,

between rich and poor countries,

between “old” and “new” mining countries

is important, as is cooperation

between governments and industry.

Corporate Concentration

The mining industry has been going

through a consolidation phase during the

last couple of years. Due to the long-term

nature of exploration and mining investment

the supply response has been slow,

and it will take years to make up for earlier

under-investment. Therefore, mining

companies will continue to generate good

if not record profits and mergers-andacquisitions

pressure will continue at a

high level. The once-fragmented structure

of mining is slowly disappearing.

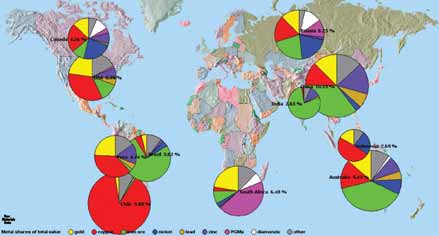

As mining gradually becomes more consolidated, a small number of companies control an increasing share of the global industry. This trend has both positive and negative aspects. On the one hand, the mining industry, new players included, must consolidate to create larger and stronger corporate entities. Larger companies are necessary to fund and pursue increasing volumes of R&D including expanded exploration. Skyrocketing energy, water and environmental costs must also be addressed. On the other hand, proper checks and balances must be in place to ensure that monopolistic powers are not created. The recent case of BHP Billiton making a hostile bid for Rio Tinto is one example of a situation where market domination in iron ore for the proposed new entity would be unacceptable and the seaborne iron ore market would no longer be free and competitive.

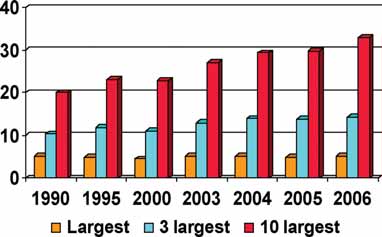

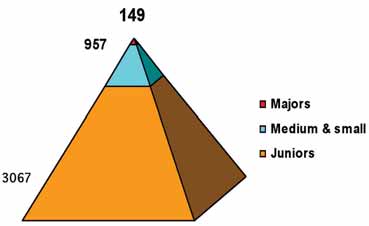

There are about 1,000 mines producing metallic ores by mechanized methods around the world, if small manual and artisanal operations are excluded. There is a huge spread between the largest and smallest mines.1 The largest 150 companies are, somewhat arbitrarily, called majors and together they represent only a few percent of the total number of companies in the sector globally. When looking at the value of the production controlled by these companies the situation is reversed; combined, they control over 80% of total global mineral production.

Some of the most active new entrants into the top league of mining companies originate in emerging countries. But, in general, developing countries do not control their mineral production—a situation that can generate considerable problems and even politically motivated calls for nationalization. It is quite possible that there will be a backlash and nationalizations will occur again after more than 20 years of privatizations. In Russia, nationalizations have already taken place in the oil sector and a move into minerals is not far away. Another example: In early 2008, the South African mine workers union called for an increased state ownership in mining. In other countries the demand for local influence and participation in huge mining profits have resulted in re-negotiated tax regimes and new royalty programs.

There will most certainly be other companies from other emerging countries following these routes.

The table below indicates how the industry would look once acquisitions proposed in 2007 have taken place. This table is based on the companies’ control of the value of mine production of nonfuel minerals in 2006 and assumes the same proportions of production in 2007 and the same relative metal price structure.

Mergers and Acquisitions

A wave of mergers and acquisitions has

swept the mining industry since the start

of 2005 and is still going strong well

into 2008. There are presently many

rumors of potential new acquisitions as

well as actual bids both friendly and hostile.

The largest of the proposed deals is

the BHP Billiton bid for Rio Tinto, which

would result in the top mining company

being almost twice the size of its closest

competitor. The new entity would control

almost 9% of the mining industry globally.

A deal would probably be conditioned

on a selloff of some of Rio’s

assets and ultimately the company

would likely control about 8% of the

value of all nonfuel minerals.

The total number of mining and exploration companies in the market economies has been increasing through the entry of optimistic junior exploration companies in recent boom years and now estimated to be more than 5,000. The restructuring of the mining industry is hampered by the fact that mines cannot be moved and hence the effects on the structure of the industry by mergers and acquisitions are limited. Emerging countries have, for many years, been the primary source of new mineral production but it is only now that companies based in these countries are gradually becoming transnational giants competing with the traditional mining majors. The power and influence of these new companies will grow also in the future. Given the continued high profits of most mining companies and the favorable outlook for metal prices for the coming years—even if prices do not remain at the extreme levels of 2006–2007 the wave of mergers and acquisitions is expected to continue into 2009.

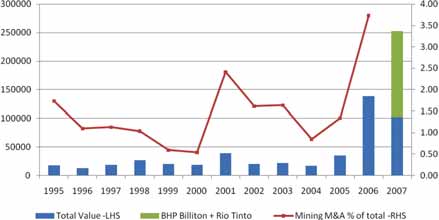

Mining M&A has historically been around 1%–2% of total M&A for both the number of deals made and also the market capitalization of mining relative to other industries. The global figure for 2006 has increased to almost 4% of total M&A activity, more than double the 2005 level. The mining industry has gradually increased its market capitalization with strong profits in recent years. This trend might end in 2008, as market caps sank during the first months following a general decline in share prices.

A few giant deals dominated the scene in 2007 as in 2006, but overall activity was high, with over 200 deals recorded. In addition to the proposed BHP-Rio Tinto merger, one more deal— Rio gobbling up Alcan after a protracted fight—is larger than all previous deals.

Since the mid-1990s there have been three crests of the M&A wave in the mining sector: in 1998, 2001 and the present one, lasting since 2005. The magnitude of the peaks to some degree depends on a few mega-deals that inflate the dollar value for a specific year. The Billiton BHP merger in 2001 together with the restructuring of De Beers and Anglo American in the same year were valued at $25 billion out of the total that year of $37 billion. In 1998, three deals accounting for over $11 billion made that year a record. If we look at the number of deals each year and exclude the deals below $10 million, the number is fairly constant at about 80 until the current level was reached.

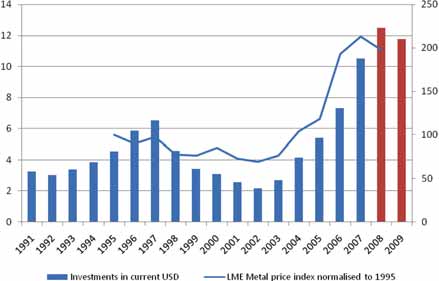

The exploration forecast is calculated on a model developed by Canada’s federal department of natural resources and is based on the fact that Canadian exploration is proportional to metal prices of the metals mined in Canada but lagging one year. Raw Materials Group has used the same model but applied it to global exploration expenditure. The price forecast is derived from forecasts of each metal done by leading analysts.

The figures do not include state-funded exploration spending, which is still important in many countries, notably Russia, the former CIS countries and China but also in well-established market economies such as Finland and India. In addition, spending on ferrous metals includes neither iron ore nor most of the ferro alloys, which in the present boom are estimated to between $0.5-$1 billion. Taking into account the strong growth in both Chinese and Russian exploration spending which has taken place in the last one to two years after high metal prices really made an impact through extreme import costs for ores, and including junior exploration companies with a budget of less than $3 million, total global exploration is estimated by Raw Materials Group to be $12 billion to $13 billion in 2007, reaching as much as $14 billion to $15 billion in 2008.

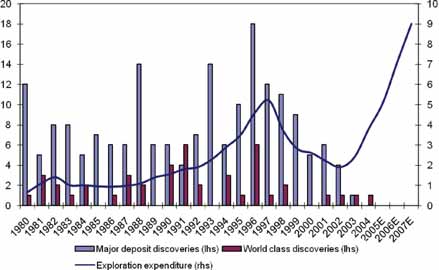

There are several structural reasons for

steady growth in exploration costs apart

from cost increases and staffing shortages

caused by the present mining boom:

• New deposits are being found in more

remote and challenging regions.

• Ore grades are continuously declining,

making discoveries more difficult.

• The most easily detected orebodies—

those outcropping or at shallow depths—

have already been located.

Increase in demand for metals and minerals makes it necessary to actually increase the speed of discovery of new deposits if total ore reserves measured relative total metal production should not decrease. Seen in this light, it is obvious that exploration activity must be increased significantly, or at least that the coming slump—which is probable judging from declining metal prices— should not be a dramatic as the trough seen in 2001-2002 if there should not be another dramatic price peak in a couple of years.

Many new actors will enter the global

mining scene during the next couple of

years. Some will be new players from

emerging countries starting their international

“careers;” others will occur

through mergers between existing mining

companies. It is becoming increasingly

important that the script for conduct and

behavior of all mining companies,

whether seasoned TNCs or newcomers, is

re-written and updated to achieve three

major goals:

• All companies must use the same script.

• Host countries shall receive their fair

and increasing share of mining profits.

• Exploration efforts must be increased.

Magnus Ericsson is chairman and cofounder of the Raw Materials Group (www.rmg.se), an independent group of mineral economists and mineral strategy/ policy analysts based in Stockholm, Sweden.