Achieving World Class Maintenance Status

Measuring and assessing maintenance performance

By Paul D. Tomlingson

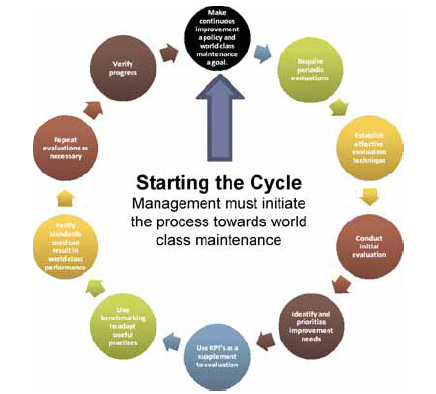

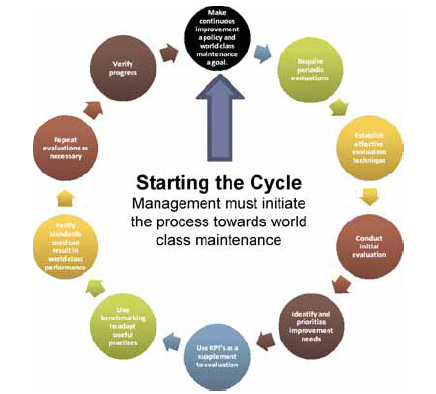

“World class” performance is the ultimate objective

of many maintenance organizations. It marks the organization as a leader in its

industry and sets it apart as the ultimate achiever. But, what is world class,

and how can it be achieved? World class maintenance could result when an organization

consistently produces reliable equipment by conducting an effective program using

accurate, timely, complete information. The challenge is to determine what constitutes

a world class maintenance organization and then derive a specific set of performance

standards that, if honestly met, universally identify the qualifying organization

as world class within its industry. Most maintenance organizations admit a need

to improve. With world class performance as a target, they should take steps to

assess their “as-is” performance status and determine what they must

improve to meet the target. Evaluation is the first step of improvement. An evaluation

establishes the current performance level by identifying those activities needing

improvement as well as those being performed well. The most important byproducts

of an effective evaluation will be the education of personnel about specific improvements

and their purpose, and obtaining their genuine commitment to helping achieve the

improvements. An effective evaluation must compare the demonstrated performance

of the subject organization against a set of standards that are consistent with

the type of industrial maintenance organization being assessed. The evaluation

procedure should be an established management practice that initially establishes

the organization’s “as is” performance level; then, at regular

intervals measures progress toward meeting the standards. Successful maintenance

is not a stand-alone activity. Maintenance planning, for example, cannot be evaluated

in isolation. It must be examined in the light of how well purchasing and warehousing

support material needs or how effectively the information system allows the planner

to manage planned jobs from inception to completion. If operations were to consistently

elect to try to meet elusive production targets ahead of making equipment available

for scheduled maintenance, poor maintenance performance (by operations default)

would be the unfortunate result. Maintenance would be equally unsuccessful if

their maintenance program were undocumented “folklore,” inadequately

communicated to other departments that want to help but can only guess how. Maintenance

would surely fail if the mine manager thought of maintenance as a necessary evil—a

cost reduction challenge to be quickly solved by an ill informed workforce reduction.

Who Evaluates?

We often think of consultants as evaluators. They can be neutral third parties

with experience in various types of operations. But, their evaluation may come

with a huge price tag and might cause prolonged disruption of mine operations.

Mine personnel might be spectators rather than participants in the evaluation

process, and the employees’ unique, pertinent and factual knowledge of actual

mine circumstances could be overlooked. Therefore, a mine should choose wisely

if they want consultants to evaluate them. And, there are evaluation techniques,

equally as effective as those provided by consultants, that are less disruptive

and costly and produce reliable results. For example: A cross-section of mine

personnel, rating maintenance against a series of performance standards that touch

on everything from mine manager- ship to production cooperation to staff department

support to preventive maintenance, planning, scheduling and the effective use

of information. If that cross-section were to consist of managers who watch all

departments interact, to staff departments that support maintenance, plus production

people who use maintenance services and maintenance themselves, it is possible

that a good picture of actual performance could result. Moreover, if each group

were represented by a vertical slice of their personnel, the results might be

even better. Suppose, for instance, that the maintenance group included the maintenance

manager, several supervisors, planners, a maintenance engineer and various craftsmen.

Consider what might result if the maintenance manager learned that a new procedure

was considered impractical by his supervisors, and the craftsmen for whom it was

intended never heard of it. The outcome of the combined ratings would confirm

that the maintenance manager should have conferred with his key personnel as future

procedures are developed. He would have learned a valuable lesson first hand and

be inclined to correct it—particularly if the mine manager has read the

same report.

The Value of Benchmarking and KPI’s

Is benchmarking a suitable evaluation technique for achieving maintenance improvement?

The idea of learning from other's good ideas or benefiting from their successful

experiences as well as avoiding their mistakes is a philosophy of long standing.

But make certain that what is benchmarked has value to your improvement needs.

Benchmarking is only a comparison of pertinent practices, not a contrast of performance.

Therefore, while helpful in the overall aspect of improvement, benchmarking alone

will not bring about the improvement necessary to achieve world class performance.

Rather, it might help to identify those organizations that have achieved it and

encourage the innovative adaptation of their best practices to the aspiring maintenance

organization. Furthermore, serious flaws exist in the prevailing notion that key

performance indices (KPI’s) are an effective performance measurement tool

and that actions based on their results can help a maintenance organization achieve

top level performance status. Key performance indices are useful in revealing

a trend toward realizing a visualized performance target. However, the field data

on which the indices are often based is usually developed and submitted by the

same people who are to be evaluated. Unless the monitoring organization can verify

the validity of the ingredient data, the resulting indices may be suspect. Agreement

on which performance indices best reveal actual circumstances can be difficult

and the logic for their inclusion questioned. For example, one popular index is

the amount of work that a maintenance organization plans. Inconsistencies abound;

preventive maintenance, for instance, is often considered to be planned and scheduled.

In reality, PM services were planned when the PM program was initially developed.

Thus, PM services are repetitively scheduled not planned on a week to week basis

as is other work embraced by this index such as overhauls or major component replacements.

For reasons such as this, the intended interpretation of indices must be established

with care. While a typical mine manager who looks at an array of performance indices

can observe relative scores, he often cannot direct a specific corrective action

as a result. By contrast, an evaluation technique built on a cross-section of

mine personnel rating a series of appropriate, pertinent performance standards

will identify exactly what is in need of improvement and establish the proper

corrective actions, by urgency and priority. To illustrate: Too little planning

often means that the PM inspection and testing program fails to find deficiencies

with sufficient lead-time to be able to plan the work rather than react to it.

If specific standards assess planning as inadequate and identify poorly executed

PM inspection and testing along with poor PM schedule compliance by operations,

the mine manager now has the right improvement target and a specific improvement

action. If this knowledge causes him to look in on a typical weekly operations

and maintenance scheduling meeting only, to find an indifferent planner talking

to empty operations chairs, he can focus on fixing the problem of too little planning,

permanently. By contrast, a single KPI simply telling him there is too little

planning only frustrates him. Performance indices are often limited to examining

only direct maintenance activities such as planning without assessing underlying

factors that influence the success of planning—quality of material support

provided by warehousing or purchasing, for example. From the mine manager’s

view, the contrast between looking at indices and reviewing the details of a well-conceived

self-evaluation is the difference between looking out the window to guess how

you are doing versus “management by walking around.”

What’s the Frequency?

Overly frequent evaluation of weekly indices soon loses its appeal—similar

to the work order procedure that requires reporting of delay causes for each job.

Such procedures often get off to an enthusiastic start but are ultimately abandoned.

Problems revealed in this week’s index are seldom able to be acted on in

the short interval. By contrast, self-evaluation applied at longer intervals (~6

months) is less intrusive and more anticipated. Random sampling, one of the principles

underlying a self-evaluation, is more realistic than KPI’s. It is welcomed

as an opportunity to see how the organization stacks up against a pertinent series

of performance standards. Thereafter, a periodic repeat of the evaluation acts

as a report card on improvement progress. This report card is also welcomed because

it represents the progress made by the same personnel who identified necessary

improvements needs at the start of the self-evaluation process. Most importantly,

self-evaluation allows dedicated, skilled craftsmen and others to participate

in the assessment process. They seize the opportunity to offer frank and objective

assessments knowing that otherwise they might never have been asked. When combined

with the responses of the balance of the cross-section of the mine population,

the result is a more reliable assessment with specific insights into the right

corrective actions. If an evaluation were to cover hundreds of performance standards,

all rated by a crosssection of knowledgeable, caring mine personnel, the results

could help propel maintenance toward positive corrective actions leading to the

real attainment of world-class status. Repetitions of the evaluation at thoughtful

intervals would act to measure interim improvement progress toward that goal.

A self-evaluation—assuming it contains the right standards—has considerable,

direct improvement potential. Personnel know the mine well. They are familiar

with people in other departments and how they must interact successfully. As they

rate the standards, they are likely to be frank and objective in identifying and

prioritizing actions or procedures that should be changed or improved. They know

that they are going to be directly affected by the potentially beneficial outcome

they visualize. They concurrently make a genuine commitment to help implement

changes they see as practical and necessary. Unlike spectators to third party

evaluations by consultants or employees who observe the irate mine manager’s

demand for more planning, self-evaluation participants can impact their own futures

directly and they know it.

Defining Evaluation Standards

An inevitable question is: What standards should apply, and who says they are

the right ones? Developing the right standards is a task that must precede any

evaluation effort that compares current performance against them. The standards

must be based on a well-conceived, fully documented, well-understood and effectively

executed maintenance program. A well–defined and effective maintenance program

spells out the interaction of all departments as they request or identify work,

classify it to determine the best reaction, plan selected work to ensure it is

accomplished efficiently, schedule the work to ensure it is performed at the best

time with the most effective use of resources. In addition, the maintenance program

specifies how work is assigned to personnel in a way that assures each person

has a full shift of bona–fide work. Then, as work is performed, the program

establishes work control procedures to ensure quality work, completed on time.

In addition, the program specifies how completed work is measured to ensure timely

completion, under budget with quality results. The maintenance program should

also prescribe a means of periodic evaluations to identify and prioritize improvement

needs. The maintenance program is the soul of the overall maintenance effort.

It defines the basics of what maintenance does, who does what, how they do it

and why. When the program is well-conceived, fully-documented and well-understood

across the operation it will be effectively executed and produce quality results.

By sharp contrast, a maintenance department uncertain of these basics cannot determine

how they will organize or even select the right information systemmuch less use

it effectively. The end result is a totally reactionary maintenance effort. A

quality maintenance program is fundamental to the development of performance standards

and to the ultimate success of maintenance. Few maintenance organizations have

such programs, fewer yet have documented them and very few have bothered to explain

how they do their work to even their own people. Customers in operations and supporting

departments guess at what is expected of them, fail to be of proper assistance

to maintenance and, in exasperation, usually ask, “what program?”

Mine managers often express the same frustration. For maintenance departments

without such programs, life is difficult. Developing standards is out of the question

and attempts to adopt advanced strategies like reliability centered maintenance

(RCM) or total productive maintenance (TPM) fail most of the time. Similarly,

implementation of modern techniques for improving equipment reliability may fail

as well. More, importantly, the fundamentals of maintenance management are never

mastered. A totally reactionary maintenance organization can never hope to achieve

top level performance. But, the organization that has a well-defined program can

establish the standards it must meet and, with the aid of an established self-evaluation

procedure, move toward and achieve world class status.

Paul D. Tomlingson is principal of management consulting firm Paul D.

Tomlingson Associates (www.tomlingson. com). He can be contacted by e-mail at

pdtmtc@sprynet.com